Hubble telescope observes a hungry supermassive black hole devouring a star

While some stars reach the end of their lives with a bang, exploding in an enormous supernova, others end in a whimper, puffing up and throwing off material before shrinking and cooling to a small core. But very rarely, some stars suffer a more drastic fate as they are ripped apart and devoured by a hungry black hole.

Such an event happens only a few times every 100,000 years in a galaxy with a dormant black hole at its center, but recently, one such event was caught by the Hubble Space Telescope. Researchers observed the final few moments of the life of a star that wandered too close to a black hole nearly 300 million light-years away and was devoured, sending out a burst of light in an event named AT2022dsb.

“Black holes are very messy eaters.”

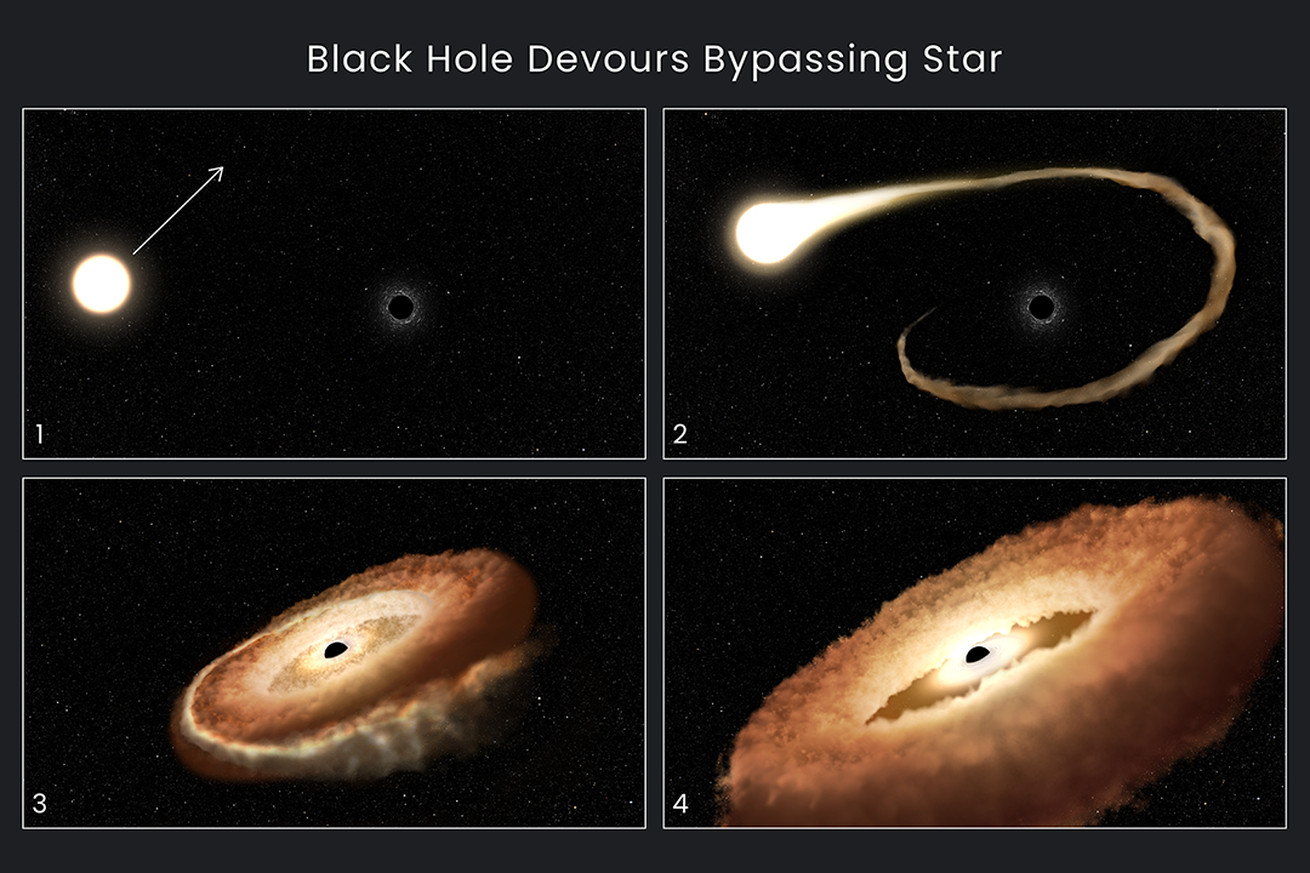

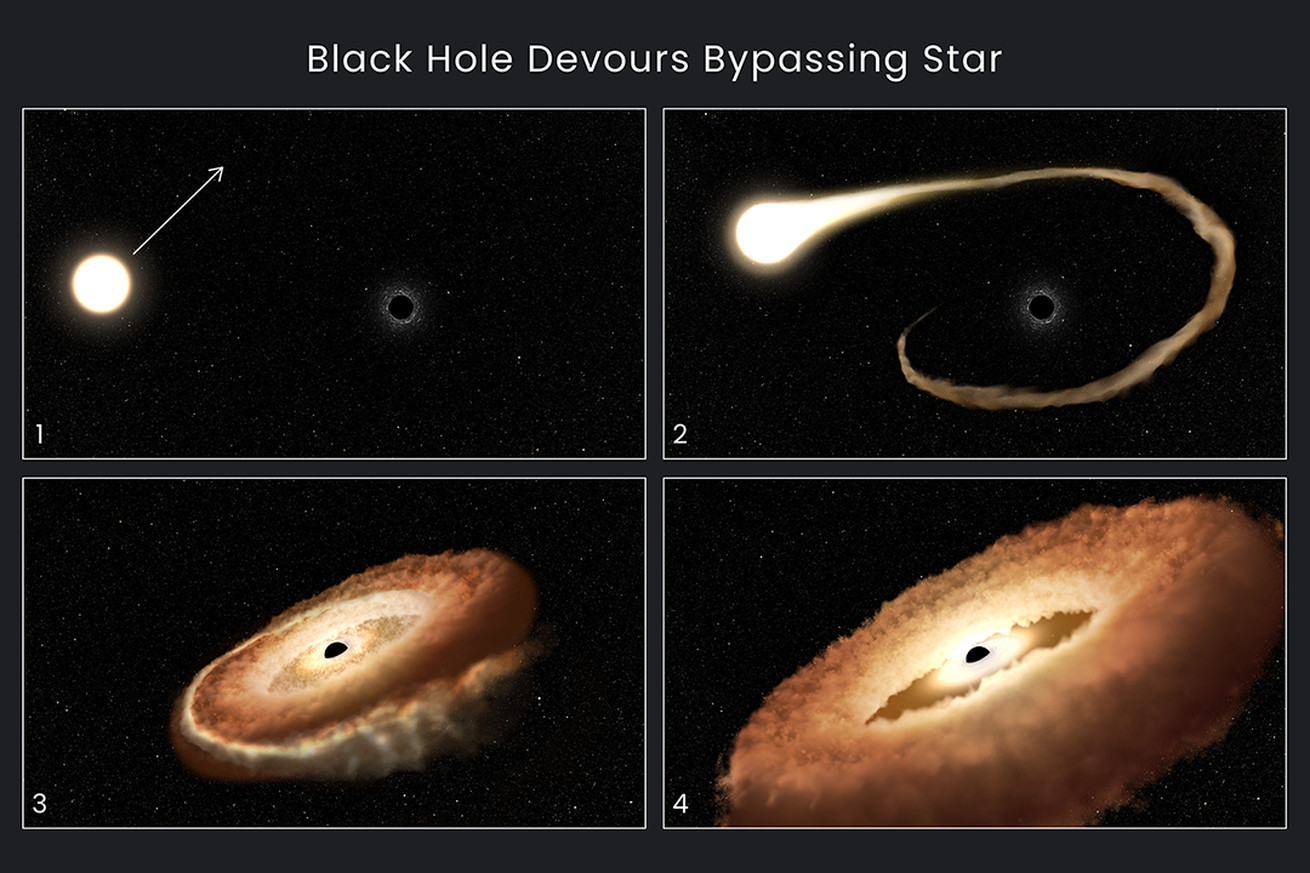

The shredding of a star by a black hole is called a tidal disruption event and is caused by the tremendous gravitational forces of a supermassive black hole. These huge black holes lurk at the center of galaxies and can pull layers of gas off a star that gets too close. Eventually, the star is shredded completely, and its remnants are pulled into a disk of matter around the black hole called an accretion disk — from which the black hole feeds.

“Black holes are very messy eaters,” one of the researchers, Emily Engelthaler of the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, explained at the American Astronomical Society meeting on Thursday, January 12th. “They’re eating this accretion disk — this doughnut-shaped thing — from the inside, and they’re eating too much and spewing out radiation as they do so, making this accretion disk puff up into a nice, big fat doughnut.”

Some of the radiation given off by these events zooms away in the form of jets, but this research focused on the radiation that is coming through the accretion disk itself. The researchers used Hubble to look at ultraviolet light coming from the star, using a technique called spectroscopy to break that light into wavelengths to see which had been absorbed. That allows them to figure out what kind of elements were present and build up clues about what is happening inside the bright, hot chaos around the black hole.

Such an event happens only a few times every 100,000 years in a galaxy with a dormant black hole at its center

It’s not often that such events are observed in the ultraviolet because this wavelength is easily blocked and therefore difficult to gather data on. A telescope outside of Earth’s atmosphere was required. “Ultraviolet is very bad at getting through atmospheres, which is great for us but terrible for observation. So we have to use a space telescope,” Engelthaler said.

The researchers wanted to know how the star and the black hole changed over time, so they made a series of observations over several months. They found that temperatures in the disk dropped over time and that stellar winds whooshed away from the event and toward us, traveling at tremendous speeds of 20 million miles per hour, or 3 percent the speed of light.

However, the spectra that the researchers collected weren’t stable — they varied considerably over time. It could be that this is simply because the source being studied is very far away so the signal became hidden among the noise. Or it could be that the donut of material around the black hole actually became thinner and the amount of material pulled in by the black hole dropped.

The researchers are still working to unpick all of the data they collected. “We really are still getting our heads around the event,” said fellow researcher Peter Maksym in a statement. “You shred the star and then it’s got this material that’s making its way into the black hole. And so you’ve got models where you think you know what is going on, and then you’ve got what you actually see. This is an exciting place for scientists to be: right at the interface of the known and the unknown.”