India’s gig economy drivers face bust in the country’s digital boom

Suneeta Kohli, a female Uber driver in New Delhi, had her account suddenly disabled one evening while she was en route to pick up a rider in a southern part of the capital city.

“I was reaching the destination, but it took some time due to heavy traffic. The ride eventually got canceled. But after that, my account was blocked,” she recalled.

Kohli, who has been driving for Uber for nearly four years and covers a distance of 112-124 miles daily, received a message saying her account had been blocked due to “an excessive number of fraudulent trips.” Kohli claimed that she had not taken any such fraudulent trips but pointed out the blocking happened to occur just days after participating in the country’s first women-driver strike in the capital in December. She was one of the prominent faces during the hours-long protest.

As the sole earner in her family and a single parent of two daughters, Kohli said she often avoids taking leaves because it significantly impacts her household budget. Kohli’s account was restored, unlike some of her co-protesters who remained blocked on the platform for some days. They believed it was due to their recent protest, though Uber denied this and put the blame on their service.

“There is no truth to it. No driver IDs were blocked related to the protest,” an Uber spokesperson said.

Many gig workers in India, like Kohli, frequently experience deactivation of their accounts on platforms, often for simply speaking out about issues. However, the platforms tend to evade accountability for these actions. South India’s Telangana Gig and Platform Workers’ Union (TGPWU), which has more than 10,000 members, receives 25-30 cases of workers facing account deactivations by platforms every week. Sometimes, platforms block the accounts of these hard-earner workers for as many as four weeks (TechCrunch reviewed some screenshots shared by some affected workers).

Account blockings and platform delistings are not limited to India, as drivers in the U.S. and Europe also face similar actions regularly. Nonetheless, gig workers in India who work with platforms such as cab-hailing companies Ola and Uber, as well as food and grocery delivery apps such as Swiggy, Zomato and Zepto and service platforms including Urban Company, have many pain points that are either unique to or quite significant in the South Asian nation, which aims to become a $1 trillion digital economy by 2025. The problems are chiefly related to declining income, increasing variable expenses and lack of welfare schemes and social security. As the country is becoming more digital and has attracted global tech companies and startups, gig workers’ pain is growing in severity — and so are their protests.

TechCrunch has spoken with several workers associated with cab aggregators and food delivery platforms, spokespersons of their local unions and researchers closely looking at their lives to understand their concerns better.

The beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, followed by nationwide lockdowns and restrictions, helped internet-based platforms grow their businesses in India — just like in many parts of the world. But that growth also made jobs of gig workers in the country more challenging: They saw a decline in payouts and increased competition with the surge of new workers joining these platforms after being made redundant from salaried roles.

Per the details shared by the Indian Federation of App-Based Transport Workers (IFAT), which has amassed more than 35,000 members across the country since early 2020, food and grocery delivery platform workers earn an average of between $0.18-$0.24 per order. This declined between 43-57% from the $0.42 they were getting until the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Companies have also increased their delivery area radius from 2.4 miles to 12.4 miles, the workers’ union said, which could mean drivers take longer journeys, and thus fewer trips in a working day.

Cab drivers on SoftBank-backed Ola and Uber get the equivalent of between $6 and $10 daily. This comes after deducting the commission cab aggregators take for each ride they offer drivers. IFAT said the aggregator cut previously was 20%, though it increased to 25-30% following the initial pandemic phase.

Although payments to cab drivers have stayed the same in the last couple of years, the increased commission rate has reduced their net earnings, the union said.

On the other hand, delivery workers who deliver food and groceries get anywhere between $4 and $6 per day. They used to earn between $6 and $10 daily until the beginning of the pandemic, IFAT’s data shows.

A Swiggy spokesperson refuted the claims of seeing a decline in payments and said the earnings of its delivery workers increased by 22% in 2022 compared to when the pandemic started in 2020. The spokesperson said the earnings comprise three components: per-order pay, surge pay and incentive pay. The startup also shares 100% of tips given by consumers to its delivery workers, the spokesperson said. The company, however, did not share any exact earning details to justify its claims.

Platforms claim they offer flexibility to log in and out to their workers. “Statistically, 95% of Swiggy’s delivery executives who do a shift of 8-9 hours, hit their delivery targets and earn their weekly incentives,” the Swiggy spokesperson said.

However, Shaik Salauddin, national general secretary of IFAT, told TechCrunch that workers with food and grocery delivery and cab aggregator platforms work at least 12-14 hours a day to generate the average income. He worked as a cab driver until September last year.

On top of seeing the dip in their earnings, workers need to pay more for the fuel their vehicles require to enable these services, as the country has hiked petrol and diesel prices multiple times in the last couple of years. The price of compressed natural gas (CNG), which fuels most cabs in the country, has also increased a whopping 86%, from $0.52 in December 2020 to $0.97 last month.

Worker unions have been demanding that platforms limit the radius within which they get their customers — for both deliveries and cab bookings — as workers sometimes travel miles to reach their customer destination. This incurs unnecessary fuel consumption and time. But no significant move has been seen from the platforms’ side.

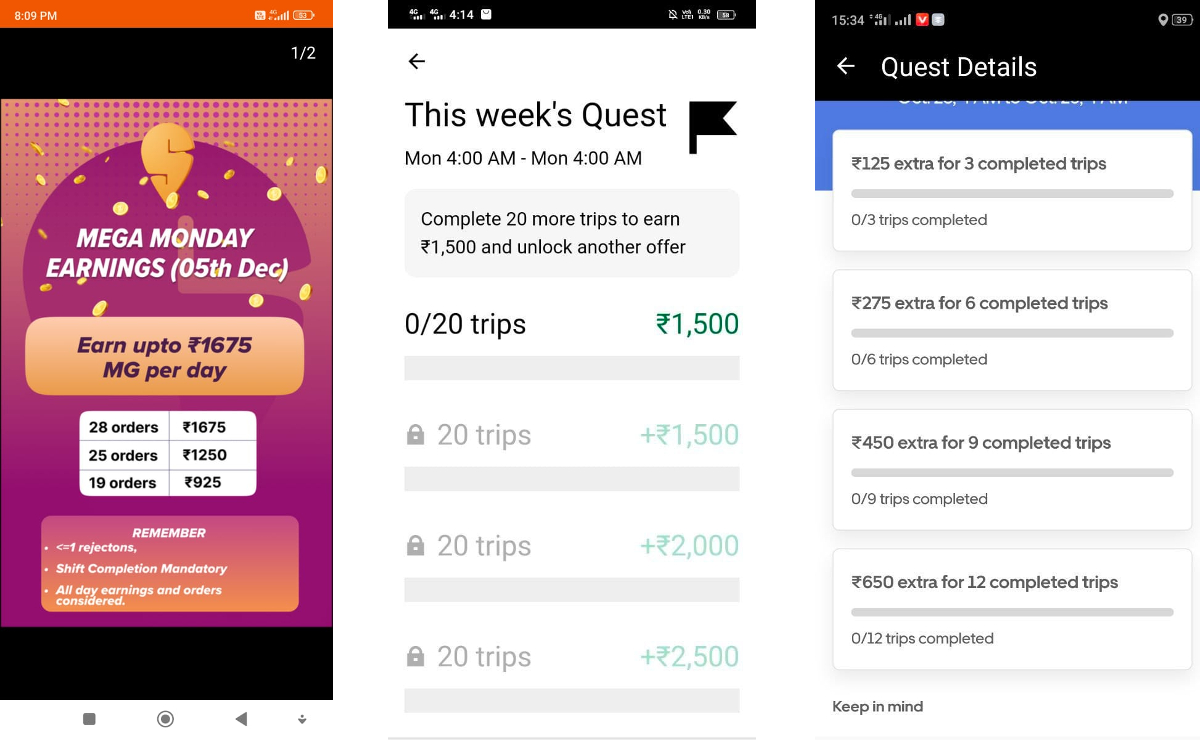

Gig work platforms try to gamify their models to push workers and convince them to do their jobs rigorously, Salauddin said. However, as the workers become more experienced and see no significant incentives coming out of that platform-driven stimulus, they start getting frustrated.

Swiggy, Ola and Uber app screenshots (from left to right) showing gamifications on their platforms encouraging workers to continue to work hard. Image Credits: IFAT

Platforms used to have managers and team leaders in place to reduce the frustration of their workers and listen to their problems. But to avoid the costs of keeping active last-mile support, most platforms have switched to automated or remote ways to readdress worker issues, according to workers’ unions.

“A zone manager is now replaced with a remote operation control person,” said Rikta Krishnaswamy, Delhi-NCR coordinator of the All India Gig Workers’ Union (AIGWU).

She said that most platforms provide a web-based form or redirect workers to a call center executive who has no power or information to solve any reported issues.

“Whenever a worker faces a challenge, it’s very hard for them to get recourse from anywhere. Most of these big platforms are geared toward alleviating customers’ grievances,” said Aayush Rathi, research and programs lead at the Centre for Internet and Society.

Platforms claim they have multiple channels to communicate with their workers. The Swiggy spokesperson said it has fleet managers as the primary contact for workers to raise their concerns and feedback and sourcing and onboarding centers as the first point of contact for workers joining the platform and act as channels to direct queries and concerns to the startup through its representative. The spokesperson also said that it hosts delivery executive townhalls at a hyperlocal level, as well as offers in-app comments on the partner app and 24×7 Swiggy hotline support.

Nonetheless, several workers still find it challenging to convey their demands.

Platform companies call gig workers “partners,” but to get maximum business from these so-called partners, platforms use performance-based ratings and algorithms. Workers take some time to understand these moves. But even when they get them, most workers find no solution to make things easier and continue to live under the pressure that platforms put through ratings and algorithms.

“I don’t see an option to move away from this business as what else we can do. What will I do with my car that is still on installments? I couldn’t give it to someone to drive,” said Kohli.

In addition to the ratings and algorithms, workers need to fulfill specific targets in their service — whether they are into food or grocery deliveries or are running cabs. Examples can be fulfilling tens of deliveries or completing tens of trips in a single day.

The imposition of excessively high targets, combined with gamification and penalties, can sometimes lead to dangerous situations and accidents, resulting in deaths in some cases. This is a growing concern, particularly among delivery workers — including those enabling quick deliveries — who operate two-wheeled vehicles on public roads and feel pressure to meet their grocery and food delivery targets.

“We’ve seen terrible accidents, including loss of lives of workers, just because they don’t want to get a bad customer rating,” said Krishnaswamy.

In a few cases, the mental pressure build-up due to tainted working conditions forces workers to commit suicide.

According to the data recorded by TGPWU, at least 10 cases of Ola and Uber drivers committing suicide have emerged in Telangana, which is home to offices of big tech companies, including Google and Microsoft. Additionally, Indian media outlets have reported that some delivery workers across the country have been killed in road accidents while delivering food and grocery orders.

Platforms claim to offer insurance and support to their workers, though unions including AIGWU, IFAT and TGPWU claim these are of little to no use.

Companies only respond to issues and help drivers avail support including insurance once they appear in some media reports, one of the delivery workers, who did not want to be named, alleged. The process of claiming insurance for gig workers can be so cumbersome and time-consuming that many workers ultimately choose not to pursue it.

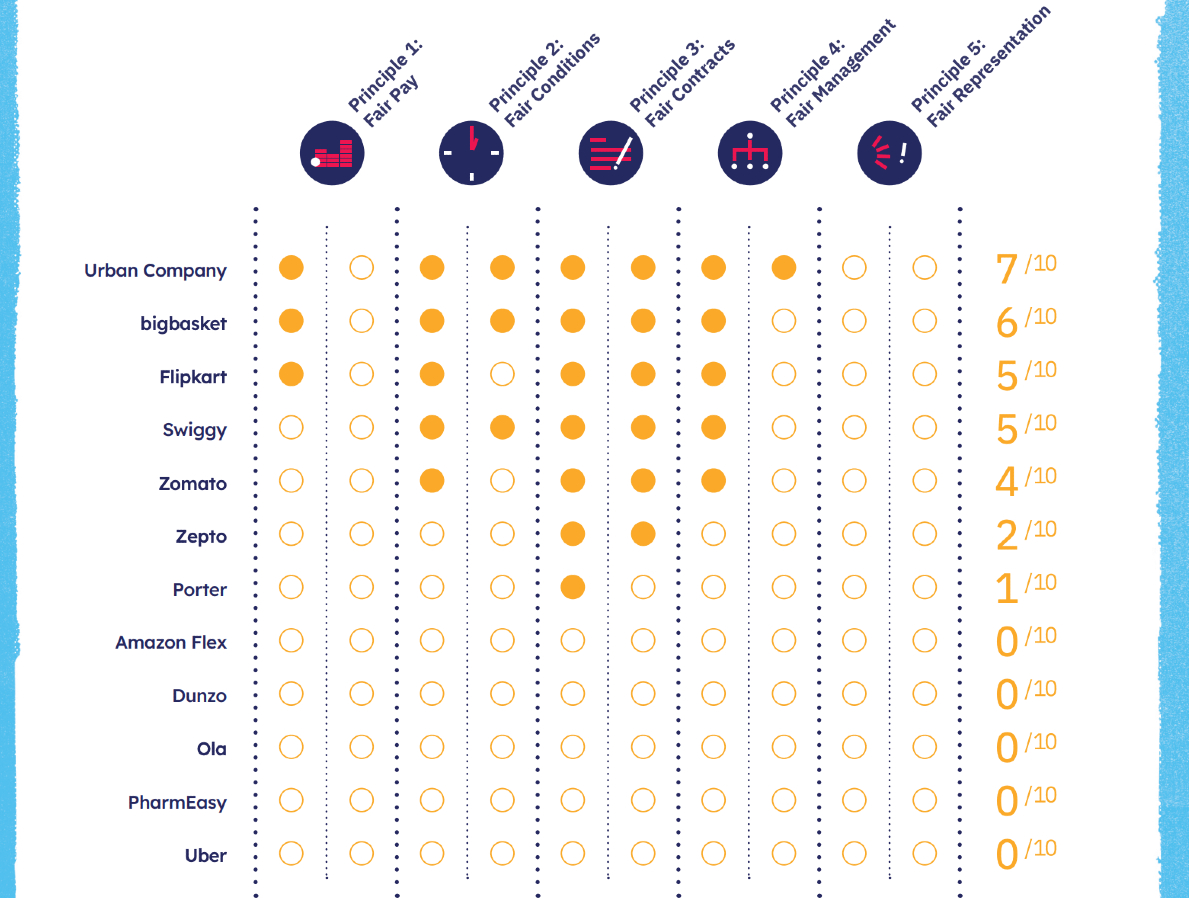

Research firm Fairwork India recently blasted platforms, including Ola, Uber, Dunzo and Amazon Flex, for their poor conditions for gig workers.

Of the 12 platforms it studied, the firm awarded the first point to Big Basket, Flipkart, Swiggy, Urban Company and Zomato under its “Fair Conditions” criteria “for simplifying their insurance claims processes and for having operational emergency helplines on the platform interface.” Others are found not to have such fair conditions. The five platforms that were found to have “Fair Conditions” for work were also noted to have other key aspects, including giving fair pay and having fair management.

Fairwork India 2022 ratings suggest some of the ongoing issues with gig platforms. Image Credits: Fairwork India

Balaji Parthasarathy, IIIT Bangalore professor and lead investigator for the Fairwork project in India, told TechCrunch that no platform from the 12 they studied was willing to talk to or acknowledge the need to speak with a worker collective. Union leaders at IFAT and AIGWU have also echoed Parthasarathy’s words and said that most platforms do not communicate with them to understand workers’ problems.

In March last year, Uber formed a Driver Advisory Council in India to mimic the model of a traditional union. The company claims the Council has 48 drivers from six cities and aims to “facilitate a two-way dialogue between Uber and drivers.” The Council has a third-party review board led by the Bengaluru-based think tank Aapti Institute. It has convened three times since its inception and taken up issues on earnings, product enhancements and social security, among others, the company spokesperson said.

“Uber has always met with driver partners to listen to their feedback about their experience with Uber and ensure we take that into account when making product changes and formulating policies. During COVID, we engaged with the driver community specifically to ask them how best to disburse emergency relief funds,” the spokesperson said when asked whether the company has ever communicated with existing driver associations such as IFAT and AIGWU to understand driver concerns better.

The Swiggy spokesperson said it engaged with all the delivery workers “directly and consistently through multiple channels.”

“At Swiggy, we like to keep our communication and engagement open to address our delivery executives’ concerns,” the spokesperson said when asked about the startup’s communication with driver associations.

Unlike Uber and Swiggy, a Zomato spokesperson has said that it had engaged with IFAT and AIGWU.

Issues with gig workers in India manifest when we look at women workers who need to pay onboarding fees again when they come back after maternity leave or regularly suffer due to the lack of public toilets in the country.

Most of these women workers are single parents and sole earners in their families.

Earlier this month, a female Uber driver in New Delhi was allegedly assaulted by some local gangsters while taking a passenger early in the morning. The attackers broke a glass bottle and used the shards to cut the woman’s neck, causing her to receive seven stitches.

“I was not in a condition to call anyone at the time, but I was on duty when the incident happened,” she said.

She added that Uber did not check for her well-being hours after the attack, and the police took 25 minutes to reach the spot. Local drivers nearby came to her aid and called the ambulance.

When reached for a comment on the matter, the Uber spokesperson said the company was in touch with the driver.

“What this driver went through is horrifying. We are in touch with the driver and wish her a speedy and full recovery. Her injury-related medical expenses will be covered under Uber’s on-trip insurance provided through a third-party insurance partner. We stand ready to support law enforcement authorities in their investigation,” the spokesperson said.

“Platforms do nothing for our issues,” said Sheetal Kashyap, a woman Uber driver who participated in the Delhi protest in December along with Kohli.

She told TechCrunch that before sitting down in the capital, the women drivers’ group tried reaching out to the company by visiting its offices in Gurugram. Instead of being granted a meeting with the management, the group was met with bouncers at the office who were unable to offer assistance, according to the driver’s account.

The drivers also attempted to convey concerns of women drivers to the state government. However, they did not receive any response, which ended up kicking off their protest, which has not yet seen any fruitful results.

Kashyap said that women drivers in the state drive 16 hours a day to earn enough to pay for monthly installments of their cabs and meet their family expenses.

The cabs in Delhi have a panic button to help riders in an emergency since a driver reportedly raped a passenger in 2015. Once pressed, cab companies claim that the button initiates alerts to the state transport department and law enforcement agencies. Some reports suggested that most cabs do not have a functioning panic button. Nevertheless, the option is explicitly given to riders and is not meant to be used by drivers. Uber has, however, offered an in-app emergency button for drivers to let them connect with local authorities if they need assistance.

Kashyap said the state government takes money, which in her case is around $85, from drivers for the panic button each time it passes their vehicle’s fitness.

Sporadic strikes — a state of affairs now

Frustrated workers often choose to raise their concerns through strikes and sit-downs. In a recent incident, thousands of delivery workers associated with SoftBank and Goldman Sachs-invested Swiggy sat on a strike in South India Kerala’s capital Kochi that lasted 44 days. The workers demanded changes such as an increase in their payments, the addition of late-night payment surges and the appointment of zonal managers.

The sit-down, which was originally aimed to be “indefinite,” disrupted Swiggy’s service in some parts of the state. The food delivery company, though, fixed that disruption by bringing workers from a third party. This has become a general practice among food delivery platforms to deploy third-party workers to avoid outages if their motorists strike. Swiggy also reached out to the court to seek police protection of its office premises, employees and third-party workers. Eventually, the startup convinced the workers protesting to call it off — without accepting their demand or giving any confirmation in writing.

The Swiggy spokesperson said that in Kochi, the weekly payout of its delivery workers increased close to 20% in the last 12 months and remained the industry-best. The startup “initiated positive dialogues to convey these details and assuage their concerns about the payouts and earning opportunities,” the spokesperson said, adding that its top-two delivery executives were from Kerala in 2022.

This was not the first time that workers conducted a strike against these platforms. In fact, some Swiggy workers made a similar protest in the southernmost Indian state of Tamil Nadu’s capital Chennai last year, which also resulted in a disruption in its service. But it was called off shortly after — without seeing any changes from the startup side. Similar strikes from Swiggy workers happened around the same issues in cities including Hyderabad, Kolkata and Noida as well, but workers resumed work after a few days — with hope to see some action on their demands over time.

Swiggy workers protested against their declining wages in Kolkata last year. Image Credits: NurPhoto / Contributor

In addition to Swiggy, Zomato and grocery startup Blinkit, which Zomato acquired last year, have seen their workers going on sit-downs for similar issues. The workers raising their problems through these protests have not yet received any firm resolutions.

According to Krishnaswamy of AIGWU, there is a strike every 15 days in the Delhi-NCR region. However, it seems that the platforms are not greatly affected by these protests.

“Unless you can sustain yourself for a week, you should not strike. A strike is like the last resort,” Krishnaswamy said.

Salauddin of IFAT said that workers go on strike when they feel pain. It’s the moment when workers listen to nothing and want their demands to be immediately addressed, he said.

Instead of getting significant pressure to address concerns or fulfill demands, platforms often ban accounts of workers going on strike to limit their protests. Google-backed Dunzo was last year seen threatening delivery workers to suspend their accounts permanently if they were found participating in or supporting any strikes. Swiggy also apparently took a similar action against its delivery workers protesting in a strike in December.

Unions, finding that strikes alone have not produced the desired outcomes, are now exploring alternative methods and reserving strikes as a last resort.

“These small struggles, these sporadic struggles, I am not at all belittling them. They are a crucial stepping stone to building an organization. And they’re a very, very crucial stepping stone for workers to understand how mighty the odds are stacked against them,” Krishnaswamy said.

Some protests did help workers to bring their issues into the limelight in the recent past. One such example is those associated with Urban Company in 2021. In that case, women workers were able to bend the startup to slash its commission rate and increase their service charges after protesting on the streets.

However, Urban Company later in December 2021 sued the protesting workers.

Krishnaswamy said one of those workers included a pregnant woman who faced fabricated criminal and civil injunctions due to raising her voice. The startup quietly withdrew the case in April last year because they knew it did not have any teeth in the matter, she said.

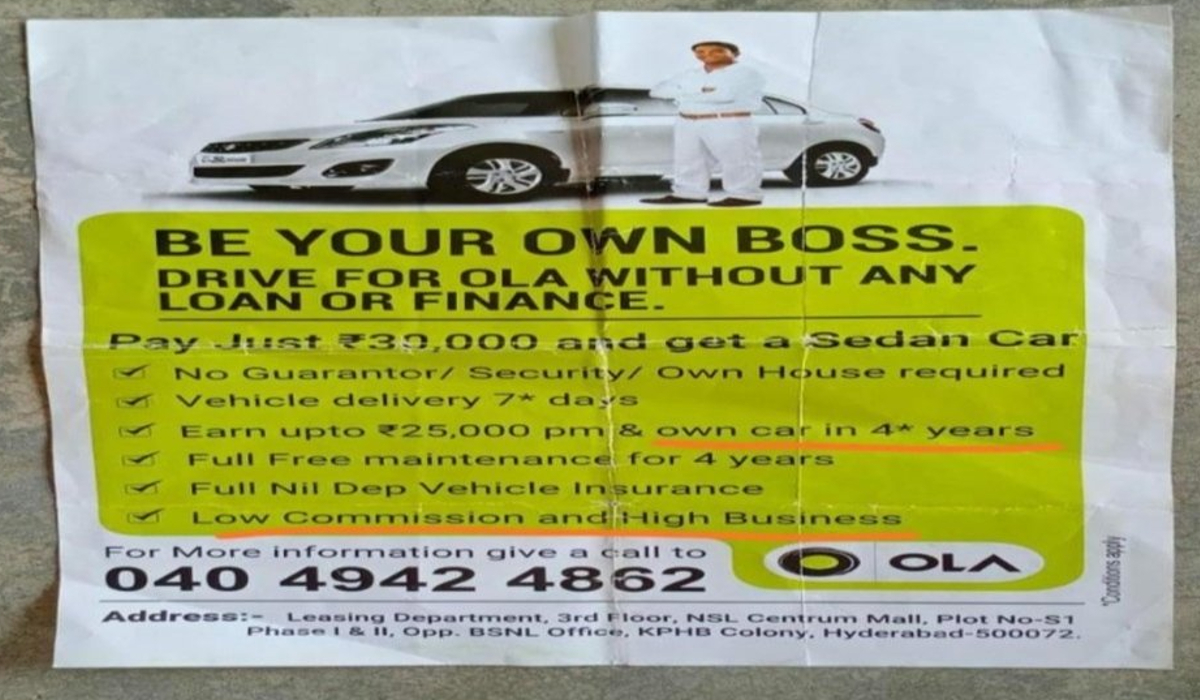

In another case, some cab drivers in 2021 protested against Ola for allegedly not returning their leased vehicles and selling some of them. Ola initially directed more than 30,000 drivers to park their leased cars in its parking spaces following the first lockdown was announced in March 2020, founder and CEO Bhavish Aggarwal tweeted at the time. However, according to the affected drivers, the startup did not return the cars when the lockdown restrictions eased in the country.

Drivers deposited a refundable security deposit between $255-$376 to get the car on lease and were required to pay some monthly rent. But that all went in vain as drivers said the startup did not return that money after trickily getting back their leased vehicles.

Marketing material shared by IFAT shows drivers were promised to earn up to $303 a month and get ownership of their leased cars in four years.

Ola lease vehicles were promised to give better earnings. Image Credits: IFAT

Ola initially convinced drivers to get leased vehicles by telling them they would be offered better business options, said Moeiz Syed, one of the affected drivers in Hyderabad, who lost the deposit of nearly $1,200 for three leased cabs. He also lost over $72 in Ola Money, which was to be transferred to his account during the lockdown.

Due to initial protests and some impacted drivers taking the matter to court, Ola did pay a partial amount in some cases. Syed, though, alleged that he did not get anything from the startup to date since he had raised some concerns with Ola earlier and participated in protests.

Ola also blocked his account and made it inaccessible. That made it impossible for him to get evidence of getting those cars on lease as the details were available only on the app, he said.

Syed, who was earlier paying six drivers to drive his cabs, had to move his house from Hyderabad to a nearby village and sell the gold jewelry of his wife to survive. He finally started working as a driver for a local goods carrier at a monthly wage of $121-$145.

Ola did not respond to a request for comment on the matter.

Slow moves from the government side

Gig work has been in the country for over a decade, and most platforms have raised billions of dollars from global investors in the last few years. Nonetheless, it was only in 2020 that New Delhi defined gig workers and platform workers as a part of its code related to social security (PDF). It is, however, yet to be operationalized and is not in force in most Indian states. Gig worker unions and researchers also call the code vague and not the ultimate move to protect the social security of gig workers.

In 2020, India’s transport ministry also amended (PDF) the existing motor vehicle law to include the businesses and practices of platform aggregators in the country. The new rules are, though, yet to be considered by most Indian states.

The labor ministry did not respond to a request for comment.

Regulatory uncertainty has a negative impact on the operations of gig platforms in India. Last year, companies such as Ola, Uber and Rapido have faced temporary bans on their services due to perceived violations of state rules. As a result, hundreds of drivers were fined for continuing to operate during the ban. The ban was eventually stayed by the Karnataka High Court. Currently, Rapido’s services are facing similar issues in Maharashtra.

Parthasarathy of the Fairwork project said there is complete silence on key issues such as fair wages and willingness or ability to bargain collectively.

“Better regulation is absolutely critical,” he said. “I don’t think platforms are going to necessarily pay attention to any voluntary code.”

In September 2021, the Indian government launched the e-Shram (e-labor in English) portal to build a comprehensive database of unorganized workers, including those who are a part of gig platforms, such as cab aggregators Uber and Ola and food and grocery delivery apps Swiggy, Dunzo and Zomato, among others. But its complicated registration process and complex requirements have restricted various gig workers from signing up on the portal, workers’ unions including IFAT said. The portal also does not support multiple Indian languages. It is limited to Hindi and English, though the country has several gig workers speaking local languages, and its constitution considers 22 official languages.

The eShram portal is available to gig workers in India. Image Credits: Screenshot / TechCrunch

The government’s data shared in the lower house of the country’s parliament in July showed (PDF) that 717,686 gig workers had been registered on the e-Shram portal as of January 2022. The number is significantly lower than the 6.8 million gig and platform workers reported by the country’s federal think tank NITI Aayog in June. The think tank also predicted that these workers will hit 23.5 million by 2030.

The NITI Aayog’s report (PDF) itself, though, does not give a clear picture of India’s gig economy, according to researchers and worker unions.

In an article published last year in response to the think tank’s report, researchers Asiya Islam and Damni Kain underlined that it carries unsubstantiated claims that gig and platform economy work has improved employment opportunities for women and people with disabilities. The report also does not hold the government accountable for developing public facilities to help create workforce participation and instead shifts the responsibility of enabling skill development and jobs from the state to private corporations, the researchers said.

“There’s this model that’s being constantly thrown at us and being proposed by the government, which is about platformizing everything like that, specifically use the term ‘platformization.’ That’s becoming a catchphrase, a popular term, where all responsibility is being abdicated by the government in favor of the platform’s doing everything,” Islam, who is a lecturer in work and employment relations at the University of Leeds, told TechCrunch.

In 2021, IFAT filed a writ petition with the country’s Supreme Court against the Indian government and platforms including Ola, Uber and Zomato, seeking to treat gig workers as employees based on the nature of their work and get them social security benefits.

“The aggregators and government should be held responsible for contributing toward the schemes that are being introduced, and a proposal can be worked out on how this can be done,” said Gayatri Singh, a senior advocate involved with IFAT on the petition.

The petition has yet to be listed for hearing in the apex court.

India versus global markets

Gig workers’ problems are not exclusive to India, as these workers in the U.S. and Europe have raised several concerns yet to be addressed. And in most countries, like the U.S.. there are no unions to speak of to represent gig workers’ interests. Nonetheless, the scale of consumption in the South Asian nation, which is the world’s second-biggest internet market, makes it different and more complex.

“There is a crisis of overproduction,” said Krishnaswamy of AIGWU.

In 2020, a judge in California ruled that cab companies Uber and Lyft must classify their drivers as employees, not self-employed. A similar judgment came from the U.K.’s Supreme Court in 2021. India has yet to see such rulings to favor its growing number of gig workers.

Fairwork’s Parthasarathy said that it is not appropriate to compare India with other markets directly as the law around the gig economy is gray around the globe.

“What drives people to work on platforms here is different from what drives people to work on platforms there [in affluent countries], and legal structures etc., are quite different,” he said.

Islam of Leeds University stated India’s large informal economy complicates the scenario.

The country’s informal sector employs about 80% of its total labor force and produces 50% of its gross domestic product.

“If you’re talking about the U.K., we end up comparing gig workers with workers who are in the formal economy because that’s the dominant alternative form of employment, whereas in India, that’s not necessarily the case. In India, most people are employed in the informal economy,” Islam said.

Currently, India lacks adequate measures to support its unemployed population, which often leads people to turn to delivery platforms and ride-hailing services to make ends meet when they lose their jobs or are struggling in their current employment.

“Why do our state governments not actually announce an unemployment allowance? If they do so, 90% of the workforce for these hyperlocal delivery companies will just quit and sit at home to wait out and get a better opportunity,” Krishnaswamy said.

For the past few years, India has also seen religious hatred and bigotry impacting gig workers. Last year, a Muslim Uber driver in Hyderabad named Syed Lateefuddin reportedly faced a violent attack, in which he was assaulted and his car was pelted with stones. The driver did not receive any response from Uber’s emergency services after several attempts and eventually called the police, TGPWU said.

Uber driver Syed Lateefuddin’s car was allegedly attacked with stones in Hyderabad last year. Image Credits: IFAT

Similar bigotry issues cropped up on Ola, Swiggy and Zomato as well. In some cases, customers made bigoted requests. The incidents were tweeted by a couple of parliamentarians of opposition parties, though the Indian government did not direct queries in any of these cases. Most companies also did not respond to the workers’ demands following the incidents to ensure redressal. However, Zomato founder Deepinder Goyal, in one case in 2019, publicly responded to the issue and said that they were not “sorry” to lose business if it came in the way of their values.

“We are proud of the idea of India – and the diversity of our esteemed customers and partners,” he said in a tweet.

When asked about its take on the communal hatred and bigotry on its platform, the Uber spokesperson told TechCrunch that it condemned any form of discrimination on its platform as it violates its community guidelines meant to maintain safety standards for riders and drivers.

“We have created multiple touch points for drivers to reach us in case they face a problem. Through our in-app emergency button, they can connect with the local law enforcement directly in case of an emergency. They also have the option to connect to an Uber support agent through a dedicated 24×7 phone support to share their concern,” the spokesperson said.

The Swiggy spokesperson also said that there was no place for discrimination on its platform. “The assignment of orders is entirely automated and does not make alterations based on the religion or community of the delivery executive and deter their earning opportunities,” the spokesperson said, adding that the startup barred customers from its platform who defy its anti-discriminatory policy that is displayed on the app and covers its customers, delivery workers and restaurant partners.

“Discrimination based on religion, caste, national origin, disability, sexual orientation, sex, marital status, gender identity, age or any other metric is deemed unlawful under applicable laws. Any credible proof of such discrimination, including any refusal to provide or receive goods or services based on the above metrics, shall render the user liable to lose access to the platform immediately,” the spokesperson said.

Are there any platforms that are not detrimental?

Although workers associated with various significant platforms have raised concerns due to their ongoing behavior, some new platforms are showing some care to their workers. One such platform is EV ride-hailing startup BluSmart, backed by BP Ventures, which pays its drivers on a weekly basis. Some drivers who moved from Ola and Uber told TechCrunch that they have found significantly less pressure when they started working with BluSmart. However, the Gurugram-headquartered startup does have target-based incentives and requires drivers to work regularly 10-14 hours a day, with up to two hours of break, to generate maximum earnings. Drivers are allowed to take one day off per week and one emergency leave per month, on any day of their choosing.

BluSmart CBO Tushar Garg told TechCrunch that the drivers have the liberty to get as many leaves as they may wish to take if informed in advance. They also choose on Fridays how much and when they want to drive for the coming week, he said.

BluSmart pays its drivers on a weekly basis. Image Credits: BluSmart

Unlike cab aggregators such as Ola or Uber, BluSmart operates its own fleet of EVs, which drivers must take from designated hubs each day. This model may not be suitable for those who have their own commercial cabs. “What we would do with our cab if we get on a platform like BluSmart?” Kashyap said.

Even Cargo is another example of operating differently for workers, but it is not a gig worker platform. The New Delhi-based social enterprise works as a women-only, last-mile e-commerce logistics provider. It allows workers to come to its hub in the morning, where they can access the washroom — before beginning their work.

“A lot of that kind of work infrastructure is completely missing from the platforms because they don’t consider themselves employees and therefore don’t actually provide anything to workers. That’s something that’s actually quite crucial to getting people who’ve been otherwise marginalized in the labor market, including women. This is what gives them the opportunity to enter the labor market,” Islam of Leeds University said while talking about Even Cargo.

Workers’ unions remain skeptical about new gig worker platforms bringing any key differences.

“You have to realize that these companies are answerable only to their shareholders, their shareholders only care about super profits, and super profits come out of super-exploitation,” Krishnaswamy of AIGWU said.