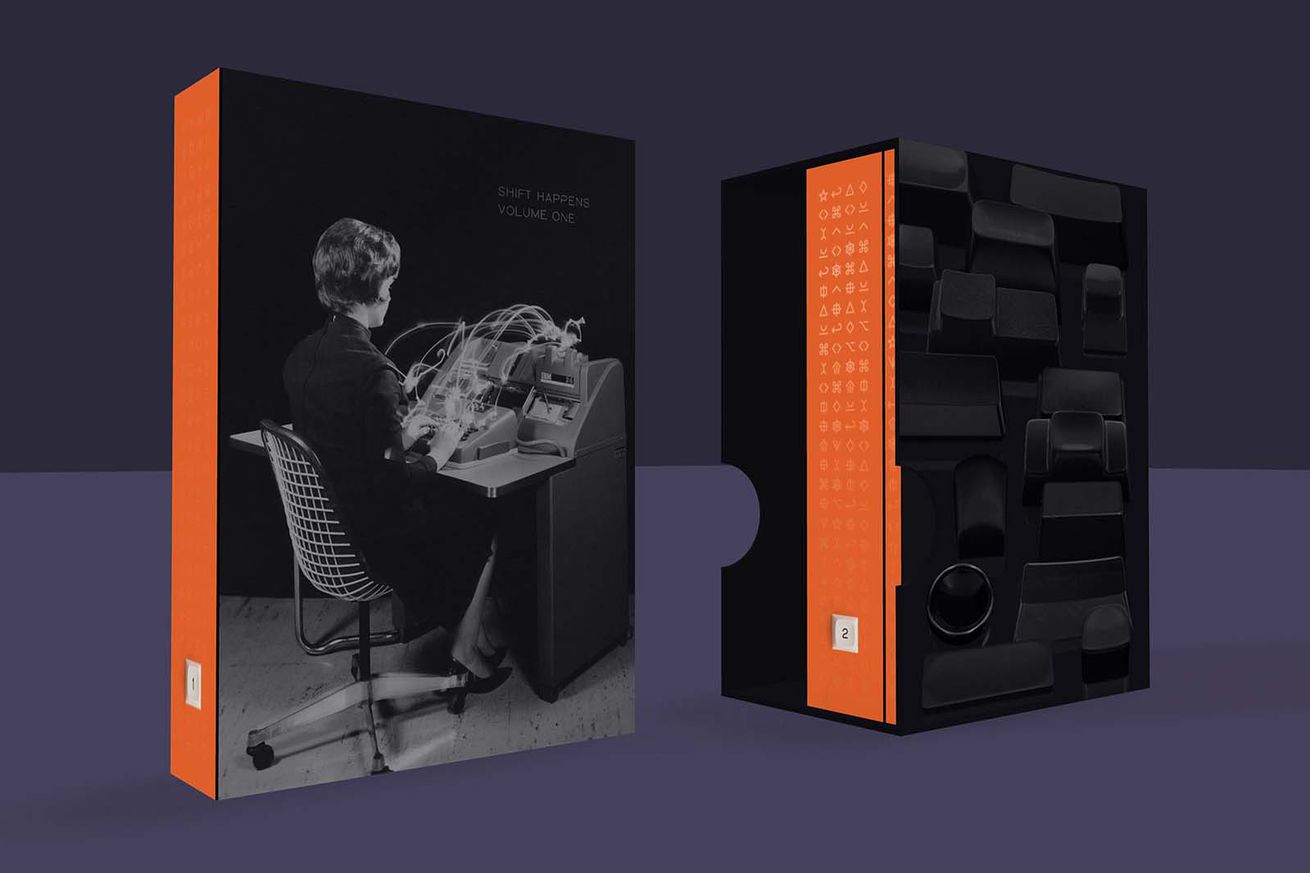

Shift Happens celebrates 150 years of typewriters, keyboards, and the people who use them

Shift Happens is a book, launching on Kickstarter today, that attempts to tell the winding story of keyboards: from the conception of the Qwerty layout a century and a half ago, through early computers, to the mechanical keyboard communities of today.

It’s the work of Marcin Wichary, a Polish designer based in Chicago who’s been blogging about keyboards for years on Medium. Part coffee-table book, filled with gloriously detailed photos of historical keyboards and typewriters, and part deeply researched textbook, Shift Happens is the work of a man that cares deeply about the design and function of a tool that’s become an essential yet oft-overlooked part of our professional and private lives.

Shift Happens delves into the Shift Wars, when competing typewriter companies had very different ideas about how their machines should carry out the most basic of tasks: creating upper and lowercase letters. It explores why Qwerty succeeded when competing layouts like Dvorak failed to gain widespread traction, and even takes the time to discuss some of the supposedly worst keyboards ever made, like those that came with the ZX Spectrum or PCjr.

I sat down with Marcin over Google Meet to discuss how the book came together and to ask whether he’s ever been able to figure out where the hell Qwerty came from (spoiler alert: it’s complicated).

The following transcript has been condensed for length and clarity.

I’d like to start by asking what your background is, and how you got into this project?

Professionally, I’m a product designer or UX designer, so always somewhere on this line between engineering and design. I’m originally from Poland, and I moved here to America a while back and got to work at Google and Medium, which was probably part of the story of my interest in keyboards. I’m currently at Figma.

When I was at Medium we were really encouraged to just write. And I started doing this partly to use the thing that I’m building, and partly to sort of try it out. At Medium, there were different typewriters in offices, almost as decoration, and there were rooms named after typewriters. I started looking at them and was like, “Oh, these keys are kind of interesting. Why is backspace on this other side? Or why is this called this? Or why does this typewriter look so funny?”

My original idea was to write a bunch of Medium stories about keyboards, but at some point, I literally counted the words. I was like, okay, I wrote these two stories. They actually ended up being a lot more than I expected. And now if I just multiplied by 10 more, it’s a book length. So I sort of worked myself into the book idea almost mathematically.

That’s hilarious. Apologies, by the way, that I’m muting while you’re talking. It’s because I have a stupidly loud keyboard in front of me, and I don’t want to ruin the transcription. Anyway, it’s interesting that the book covers both typewriters and retro keyboards and then even modern keyboards. How did you go about setting the boundaries of what you wanted to cover? Where did you draw the line?

I wasn’t initially thinking of it as a comprehensive history of all of the keyboards forever. I just wanted to center it around stories. Fortunately I found enough good stories and moments in time to actually sustain a narrative.

In half a year, the Qwerty keyboard will be 150 years old to the day. So the book kind of starts there. There were obviously typewriters before that, but they weren’t mass-produced, they weren’t as important as the first Qwerty typewriter. So basically, I’m trying to go from that moment in time to today. It’s obviously a lot of typewriter history, but it actually spent a little bit more time on the computer side, particularly since the eighties. So the book goes from early typewriters to computers, and includes a lot of the mechanical keyboard fascination of today.

I think the last thread is this sort of reflection on how keyboards were actually used throughout the decades. If you grabbed Christopher Latham Sholes, who put together the first typewriter, and sat him down today, he would know that this is a Qwerty keyboard. But the way we use the keyboard is very, very different. Typewriters used to be professional tools for people who had to go through training. Now we just chat. We talk through typing. Most keyboards are now used for just casual chatting rather than professional work.

I’ve come across many stories over the years of why Qwerty is the way it is. That’s the one about being able to type out the word “typewriter” on one row or the idea of spreading out the vowels to slow down typists. I suspect the answer to this question might be “it’s complicated,” but did you get to the bottom of why Qwerty is the way it is?

Yeah, it’s complicated. I got to what I think is the bottom, but there might be no bottom. The gist of it is that we might never know. Nothing was written down. They were running their typewriter company as a startup. Christopher Latham Sholes didn’t actually want to document some things out of the fear that they would be stolen. So they were just kind of messy. They didn’t care to document it.

So a few things that I know is that it’s not random, right? All the signs point to it being incredibly deliberate. It wasn’t to slow people down, it was to move things around with enough care that you can still type quickly and you could type really quickly on even the first typewriter. They showed the same sort of deliberation even when adapting Qwerty to other languages very early on. You could argue that they did a minimum viable product. They moved just enough so it worked.

“Things just disappear on their own if you’re not paying attention”

You can look at it and say Qwerty rolled over a lot of really interesting ideas. Like every country, every language should have its own layout, you know? But on the other hand, you can look at Qwerty and say like, well, it’s kind of cool that we have this universal standard. You can sit down to a keyboard, configure it in software, and you can write in Japanese, you can write in Chinese. I’m not saying there’s a right answer here, but I think there’s something to appreciate about Qwerty, even if you don’t like it.

You mentioned the gimmick of the word “typewriter” being on the top row, which I think from some statistical analysis… it’s not an accident. It was a deliberate marketing attempt, and yeah, it’s kind of cheap, whatever, but we’re still talking about it 150 years on!

The other side of this is Dvorak. August Dvorak analyzed all of these things that we admire about how fingers move around the keyboard and how we alternate hands and stuff like that. So why didn’t it work? And in a way the answer might be that all of the things he cared about, are important, but not important enough. He didn’t market it well. He didn’t tell the story the right way.

Remington invested in training people. Remington invested in making the keyboard feel universal and feel standardized. I think what we see in some of those layouts is that the mathematics or the physics or whatever in coming up with the layout… that’s not enough.

Are there any parts of the keyboard that have stuck around that you think have a particularly interesting history?

I think backspace is the one that’s really interesting to me. It didn’t arrive in very early typewriters because the assumption was that professionals would never make mistakes. That obviously was proven incorrect very, very quickly. So they kind of bolted backspace to the side of the typewriter. It was literally just back-space right, literally a left arrow in common parlance of today. It didn’t erase anything because how would you erase something like that? You can’t just, like, move atoms out of paper.

Buried into this key are basically 80 or more years of people trying to make typos easier to deal with. We completely forget about it today because backspace erases, and it’s not a big deal. Computers finally made it possible because in the world of electrons, it’s almost the opposite. Holding something to not disappear is the hard part. Things just disappear on their own if you’re not paying attention.

There was this beautiful moment in history where people made backspace work in a physical universe in a way that’s incredibly complicated but also kind of mind-blowing. It’s sort of like watching the last entirely practical effects movie before CGI took over.

So one story was that the co-inventor of the laser, Arthur Leonard Schawlow, actually came up with this specialized laser that would literally obliterate your typo. He actually built a prototype. He demonstrated it on national TV. He called it the “laser eraser.” It was a decade of effort of trying to make the laser eraser happen and talking to different companies and building prototypes, and it feels kind of silly because it seems like overkill, right? It feels like a folly, “lasers for typewriters.” But we had typos for decades that were hard to deal with.

IBM made what they call a “Correcting Selectric.” They put it in a name because it was so important. And basically it was this really interesting application of chemistry where they build a special ribbon so your thing would stick to paper but only slowly permeate it. So if you reacted quickly, you could lift it off the paper before it settled in.

So you had this beautiful typewriter in the 1970s where you can type a letter, you can backspace, and you can erase it. It just gets off the paper, and it’s mind-blowing. Where Arthur Leonard Schawlow tried to use lasers, they just went with two special tapes and a little bit of UI on the keyboard. We take backspace for granted today, but for most of the life of the keyboards, this was one of the hardest things to solve.

I gather you’ve interviewed some pretty interesting figures throughout the space. Were there any highlights?

I had the privilege of talking to Rick Dickenson, who designed the British computer — the ZX Spectrum — from 1982 and a few computers before and after that. There are a few keyboards that are considered the worst ever made… one of them is ZX Spectrum. It’s this small computer. The keyboard is overloaded with symbols; it’s a rubber layer on top of a membrane. Yes, you could ridicule it and yes, it doesn’t feel great. No one is going to disagree with this.

But I was talking to Rick about the process of designing it, not long before he died, and it was surprising to me how much design effort went into this. They just had a lot of constraints. It had to be cheap, it had to be made out of certain things that were available. That’s what speaks to me as a designer: that you cannot decouple design from constraints.

Another interview that I really appreciated was [University of California professor David Rempel] who’s really knowledgeable about RSI, carpal tunnel, all of this sort of like musculoskeletal issues around keyboards.

I thought it’s going to be a simple conversation where I ask him about the differences between ergonomic keyboards and nonergonomic keyboards, and what is RSI. He immediately told me that RSI doesn’t even exist as a word, so you shouldn’t use it. He said every keyboard is already ergonomic, so this is not even the right question, even the worst keyboard you have on your desk today is so much more ergonomic than any typewriter in the sixties. So people think an ergonomic keyboard is a split keyboard or, you know, or a tilted keyboard.

So in the process of the interview, we talked about the epidemic of RSI in Australia in the 1980s that I never heard about, and now it’s a big part of my book. We talked about the perception of pain and how complicated it is to even understand and measure pain. There’s this socioeconomic story of “RSI,” which existed for decades. Why did we only start talking about this in the eighties? Well, maybe because it started affecting people who were too, quote unquote, “expensive to replace.” RSI became white-collar, in a way.

I spent months, I think, just trying to do it justice in the chapter. Yes, I have really interesting-looking keyboards in the chapter with various shapes, but I think that’s only part of the story.

In addition to the written chapters in the book, I gather there’s around 1,300 photographs in there, a mix of original photography and archival shots. Can you talk about the process of putting that together?

I really want to show the keyboards. I don’t want patent drawings because that doesn’t feel like something that actually happened. And I wanted high-quality stuff, things that you would want to inspect very carefully, look at details and learn something from them. I think a lot of design, a lot of history, the details matter. There was a lot of effort there.

Taking photos from the book ended up being much more important than I thought. I think I contributed like 400 or 500 photos myself, and in that process I ended up with this strange collection of 150 keyboards. But I think the most heartwarming part of this journey was how many people were willing to help me with those photos. I had these beautiful moments of connection. For example, there was this strange joystick that was built and mounted on top of the ZX Spectrum keyboard. They use it for games, and [the ZX Spectrum] didn’t have a joystick port, so it was this funny contraption.

On Twitter, somebody mentioned that they still have it. And so I reached out to them and asked if they would mind taking a photo for this? And he’s just like, “Don’t worry, I gotcha.”

He sent me the photos a few days later and I look at them and they’re incredible resolution, they look gorgeous. I’m like, “Who are you?” And he’s like, “Oh, I just do astrophotography for a living. So I have this really expensive camera and I just pointed it towards the Earth for once, you know?”

There’s also this really cool story about how the Soviets were spying on Americans by listening to Selectric keyboards. What’s unique in my book that nobody else has is that I convinced the [National Cryptologic Museum] to take photos of the Soviet spying device. So you will see really good photos of that spying device in my book for the first time.

What’s the most memorable keyboard or typewriter you interacted with through the course of writing this book?

It’s really hard because there’s so many. In my book, I have five keyboards that I think are the most important keyboards in history. That’s the first Remington [the Sholes and Glidden], the Underwood No. 5, the IBM Selectric, the IBM Model M, and the iPhone. I think those are the pivotal moments in keyboard history.

But I snuck in one more, and that’s the one it actually talked about earlier, which is the Correcting Selectric 2. So it’s this variant of the Selectric that came a decade later, and that’s the Selectric with the magical backspace key. It is a realization of a lot of things that we do in software now, but in hardware at an extreme cost and complexity. There is, as I mentioned, a backspace that actually erases things, which, again, how would it even work if you put something in ink on paper, and yet it does!

That’s amazing, thanks so much for talking to me.

Shift Happens is available to preorder on Kickstarter now, with shipping expected around October 2023.