The Internet Archive is defending its digital library in court today

Book publishers and the Internet Archive will face off today in a hearing that could determine the future of library ebooks — deciding whether libraries must rely on the often temporary digital licenses that publishers offer or whether they can scan and lend copies of their own tomes.

At 1PM ET, a New York federal court will hear oral arguments in Hachette v. Internet Archive, a lawsuit over the archive’s Open Library program. The court will consider whether the Open Library violated copyright law by letting users “check out” digitized copies of physical books, an assertion several major publishers made in their 2020 suit. The case will be broadcast over teleconference, with the phone number available here.

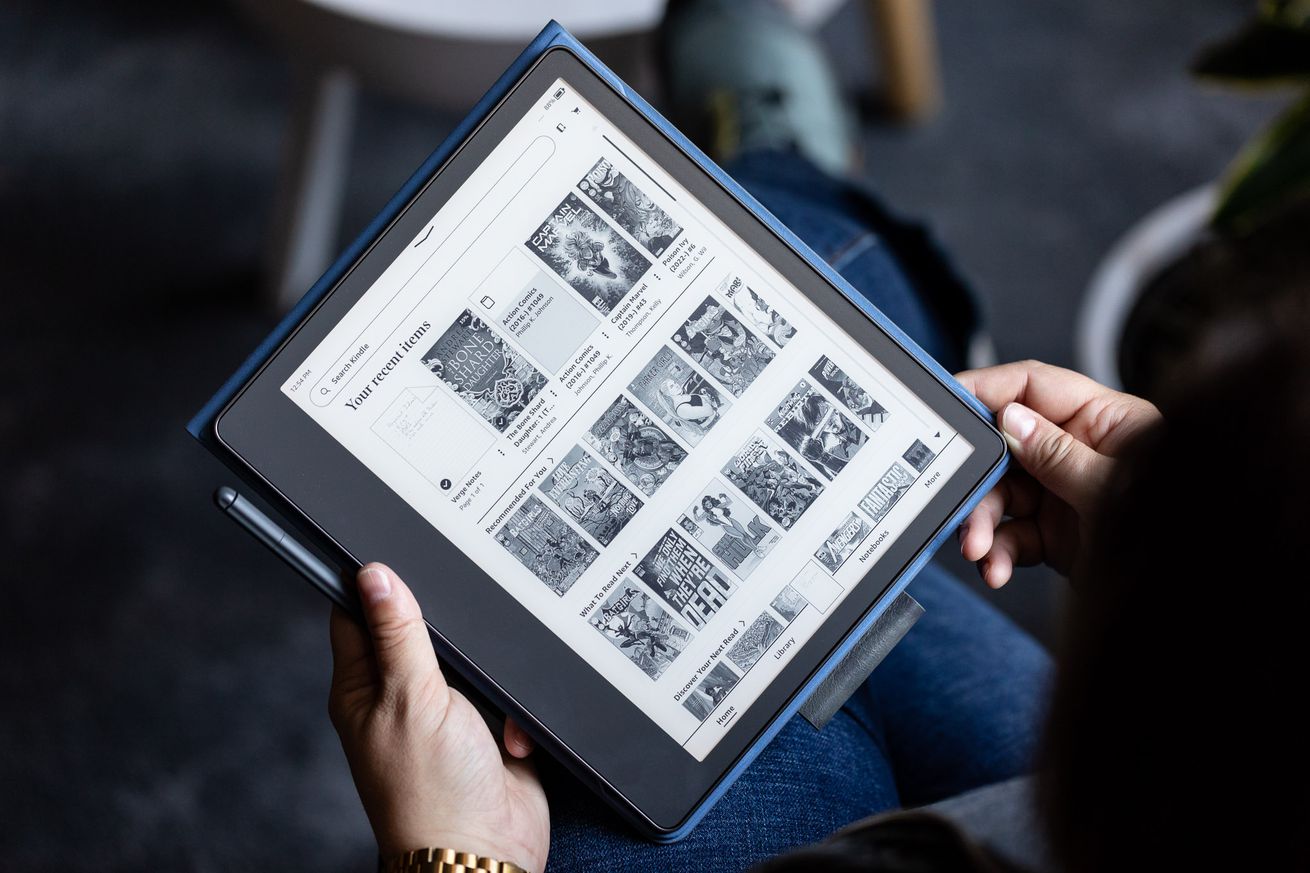

The Open Library is built around a concept called controlled digital lending, or CDL: a system where libraries digitize copies of books in their collections and then offer access to them as ebooks on a one-to-one basis (i.e., if a library has a single copy of the book, it can keep the book in storage and let one person at a time access the ebook, something known as the “own-to-loan ratio.”) CDL is different from services like OverDrive or Amazon’s Kindle library program, which offer ebooks that are officially licensed out by publishers. It’s a comparatively non-standard practice despite implementation in places like the Boston Public Library, partially because it’s based on an interpretation of US copyright doctrine that hasn’t been strictly tested in court — but this is about to change.

This lawsuit wasn’t actually spurred by classic CDL. As physical libraries closed their doors in the first months of the coronavirus pandemic, the Internet Archive launched what it called the National Emergency Library, removing the “own-to-loan” restriction and letting unlimited numbers of people access each ebook with a two-week lending period. Publishers and some authors complained about the move. Legal action from Hachette Book Group, HarperCollins Publishers, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House — a list that includes three of the print industry’s “Big Five” publishers — followed soon after.

The lawsuit takes aim at the Internet Archive’s response to the pandemic, but its arguments are much broader

Publishers took aim not just at the National Emergency Library, however, but also at the Open Library and the theory of CDL in general. The service constitutes “willful digital piracy on an industrial scale,” the complaint alleged. “Without any license or any payment to authors or publishers, IA scans print books, uploads these illegally scanned books to its servers, and distributes verbatim digital copies of the books in whole via public-facing websites. With just a few clicks, any Internet-connected user can download complete digital copies of in-copyright books.” More generally, “CDL is an invented paradigm that is well outside copyright law … based on the false premise that a print book and a digital book share the same qualities.”

The Internet Archive isn’t the only library or organization interested in CDL, and its benefits go beyond simple piracy. As a 2021 New Yorker article outlines, licensed ebooks give publishers and third-party services like OverDrive almost absolute control over how libraries can acquire and offer ebooks — including letting them set higher prices for libraries than they would for other buyers. (In 2021, Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-CA) took publishers to task for “expensive, restrictive” licensing agreements.) Libraries don’t own the ebooks in any meaningful sense, making them useless for archival purposes and even letting publishers retroactively change the text of books. And many books, particularly obscure, older, or out-of-print ones, don’t have official ebook equivalents.

Publishers can offer unique benefits, too, like the obvious fact that they let libraries get around literally scanning the books. Unofficial scans are sometimes rough and inconvenient compared to, say, a neatly formatted Kindle title. Even in a world where CDL was uncontroversial, many libraries might choose to go with official licensed versions. But there are clear reasons why libraries would want the option to digitize and lend their own books, too. CDL advocates argue it’s philosophically akin to conventional lending, which also lets lots of people access the same book while only purchasing it once.

The legal situation is much dicier and depends on how you interpret earlier cases about US fair use rules, which let people use copyrighted material without permission. On one hand, the publishers’ reference to “illegally scanned books” notwithstanding, courts have protected the right to digitize books without permission. A 2014 ruling found that fair use covered a massive digital preservation project by Google Books and HathiTrust, which scanned a vast number of books to create a database with full searchable text.

“The Open Library is not a library, it is an unlicensed aggregator and pirate site.”

On the other, services like ReDigi — which let people place music files that they owned in a digital “locker” and sell them — have been shut down by courts. So have services like Aereo, which tried to get around paying rebroadcasting fees by receiving individual over-the-air TV signals from tiny antennas and streaming them to subscribers. Both cases involved someone trying to use a digital file in an unapproved way, and neither made much progress. CDL legal theorists argue that the ReDigi case doesn’t spell doom for unauthorized library ebook lending, but until a court rules, we won’t know.

The publishers’ complaint also relies heavily on arguing the nonprofit Internet Archive isn’t running a real library. As one header put it, “The Open Library is not a library, it is an unlicensed aggregator and pirate site.” Among other things, publishers argue that the organization is a commercial operation that’s received affiliate link revenue and has received money for digitizing library books. In a response, the Internet Archive says it’s received around $5,500 total in affiliate revenue and that its digital scanning service is separate from the Open Library.

American fair use law depends on balancing several factors. That includes whether the new work is transformative — basically, whether it serves a purpose different from the copyrighted work it’s using — as well as how it affects the original work’s value and whether the new work is a commercial product. (Contrary to one popular misconception, commercially sold work isn’t automatically disqualified from fair use protections.) Whatever judgment a court makes will be specific to the Internet Archive’s fairly unique situation.

But the ruling may lay out broader principles and reasoning that could affect any attempt to repurpose physical books in ways publishers don’t approve of. Digital rights organization Fight for the Future has supported the Internet Archive with a campaign called Battle for Libraries, arguing that the lawsuit threatens the ability of libraries to hold their own digital copies of books. “Major publishers offer no option for libraries to permanently purchase digital books and carry out their traditional role of preservation,” the site notes. “It’s important that libraries actually own digital books, so that thousands of librarians all over are independently preserving the files.”

And if the Internet Archive loses the case, it could potentially be on the hook for billions of dollars in damages. That could threaten other parts of its operation like the Wayback Machine, which preserves websites and has become a vital archival resource.

Either way, it’s a potentially landmark copyright case — and the arguments of both sides are getting their first real test later today.