How do you prevent an AI-generated game from losing the plot?

Did you ever get to the end of Wizard of Oz and have notes – the nagging intuition that you could have taken down all those pesky flying monkeys or handled the backstabbing intricacies of Munchkin guild politics more effectively than Dorothy and her band of misfits did in the books? Thanks to the new AI storytelling platform Hidden Door, which plops players into TTRPG-like adventures based in their favorite literary universes, you’ll soon have the chance to walk the Yellow Brick Road however you see fit.

What’s behind (hidden) door number one

Hidden Door is both the company and the game. Hidden Door, the company, was co-founded by Hilary Mason, who is also CEO, and Matt Brandwein in 2020 with a mission to “inspire creativity through play with narrative AI.” The staff is split nearly evenly between machine learning engineers and traditional game designers, Mason told Engadget.

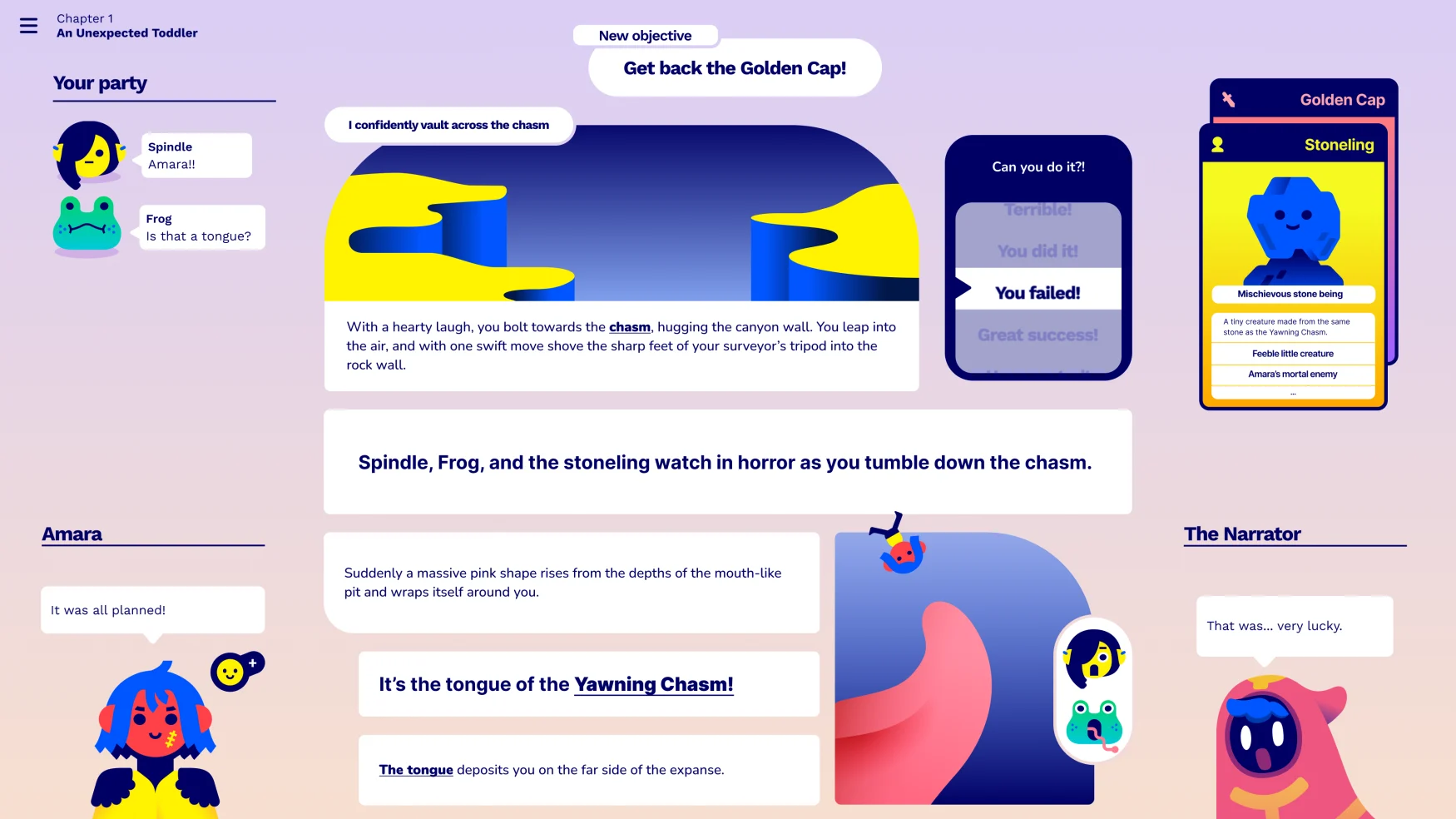

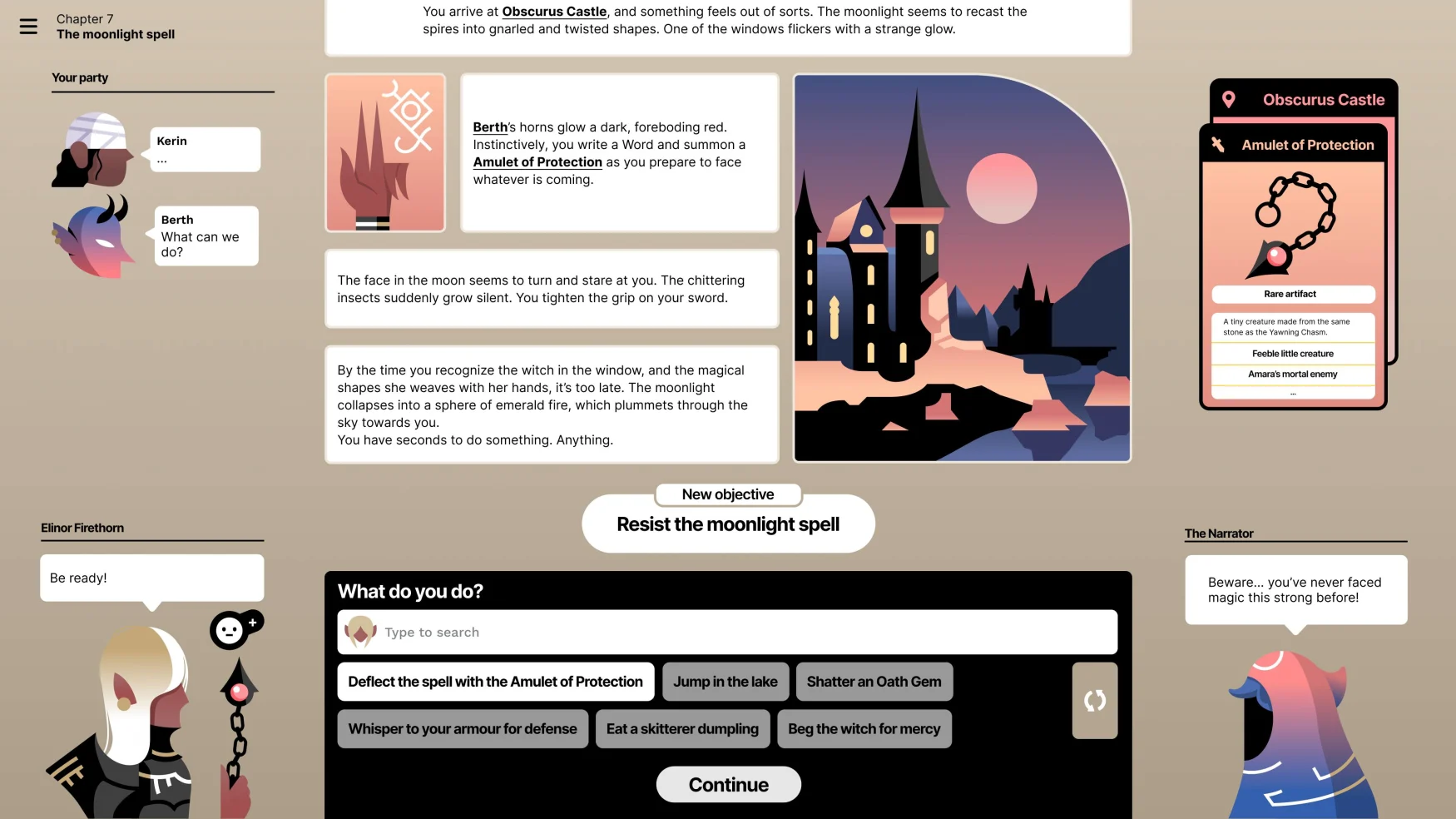

Hidden Door, the game, is the company’s currently-in-development social roleplaying narrative AI project. “[We are] trying to take all the joys of a tabletop game and allow you to play it without all the friction [of having to do it physically], and AI is the technology enabling that,” Mason said.

Leveraging the capabilities of large language models and procedural generation systems, Hidden Door creates immersive RPG campaigns using the player’s preferred IP — it could be Wizard of Oz, as was released on Monday, or Star Trek, Old Man’s War, Dungeon Crawler Carl or Agatha Christie’s assembled murder mystery library. (Just so long as the IP owner agrees to license their proprietary universe for use, which the latter four have not, the former of which has been dead long enough for it to no longer matter.)

Subscribe to the Engadget Deals Newsletter

Great deals on consumer electronics delivered straight to your inbox, curated by Engadget’s editorial team. See latest

Please enter a valid email address

Please select a newsletter

By subscribing, you are agreeing to Engadget’s Terms and Privacy Policy.

“We solve a fundamentally different, technical problem than what you would see if you were just plugging content into an LLM like ChatGPT,” Mason said. “There, what you do is take an unstructured text prompt and put it into a model which is largely a black box.”

“GPT-3 came out a few months into our project and it was clearly incredibly biased – uncontrollable and … not useful in doing something like keeping a story on the rails,” she explained. “The core of our design came from that initial desire to build a safe, controllable system for telling amazing stories.

“We realized that if we were able to accomplish our safety goals,” she continued, “we would also be able to create something controllable enough that authors would be comfortable allowing people to play in their worlds.”

The building blocks of a cursed village

Take The Wizard of Oz, for example – a public domain series originally written in 1904 by L. Frank Baum that spans 14 books in total. Hidden Door has adapted that corpus of text into an immersive in-game universe that the user, and up to three teammates, can explore. The system does so by taking unstructured inputs from the players and mapping them to the Hidden Door game state, “which is essentially a game engine that represents in a database the characters, locations, items, relationships, and their conditions,” Mason explained.

Each player starts out making a character sheet to establish their avatar’s stats and backstories. From there, the system will incorporate that data, as well as the users’ responses to in-game prompts to generate a story. Rather than create each scenario for each story from scratch every time, the story engine works on what are essentially pre-computed tropes, Mason explained, “We call them ‘story thread templates’ and they’re at the level of things like … a cursed village. Your objective for the scene is to figure out where the curse is coming from and resolve it.”

The templates serve as the basic building blocks of the story, establishing the narrative, providing structure for the players to explore and interact with the scene, and ultimately helping define when the story ends. The village curse, “you don’t know what it is,” Mason said. “You don’t know who has cursed the village or why, so it sets those things up and then it lets you loose so you explore, you interact, you set things up.”

Every template is either handwritten or generated and hand-edited by a person. The team has already created thousands of such templates. By stringing three or four such templates together, the game can create a compelling narrative arc that allows players to deeply explore these universes but while maintaining strong content and safety guardrails.

Safety (and inclusivity) first

We’ve already seen way too many examples of what goes wrong when you let a chatbot off its leash. Whether it’s spouting Nazi propaganda or making incorrect claims about space telescopes, today’s large language models are highly susceptible to veering unbidden into hate speech, “hallucinating” facts, and on occasion, bullying people into suicide. These are all issues you don’t want popping up in an all-ages game, so there are many things you cannot say while playing.

“You cannot submit anything you want,” Mason said. The system will generate suggested actions based on what the player writes, but will not accept the written input directly. The system will even give feedback and comment on what the player is suggesting, “it might say, ‘Oh, no one’s ever tried that before’ or ‘that’s gonna be really hard for you,’” she continued, but any action suggested by the system can be pre-approved.

“There is no word ever in one of those constructed sentences that’s not in our dictionary,” Mason said. “That gives us control, both for safety and for preventing inappropriate content – like, if you were to type in, ‘I joined the Nazis,’ it would reply with, ‘you get a bowl of nachos.’ We’re not gonna let you do that – and also, for keeping the story inside the bounds of believability for the in-game world.”

The company’s adherence to inclusivity is also easily recognizable in the character creation process. “We made a very deliberate decision to pull things out where we thought a model might inject bias [like a character’s pronouns],” Mason said, “such that they are essentially on a pre-computed distribution.”

That is, there is no machine learning associated with it, they’re hard coded into the gameplay. “Things like roles are in no way coupled to your avatar, your skills or anything like that. You decide your pronouns and they’re respected throughout the system,” she said. “There’s no machine learning model that is deciding that a doctor should be a he and a nurse should be a she. It’ll be randomly assigned.”

Go ahead, snoop around

Aside from committing war atrocities, telling aristocrats jokes and other forms of mass violence, players can do most anything they want once the game starts. In Oz, each instance starts at the same point in the story, right when Dorothy splatters the Wicked Witch of the East under her house. The players aren’t part of Dorothy’s direct story but exist in the same time and space. “It’s the moment most of us think about when we think about that world, which is why we chose it,” Mason said.

But from there, the player’s decisions and actions make the Land of Oz their own. ”We think of the world almost as its own character that is collectively growing as people play the story,” Mason said. “You’re discovering new locations that get generated as you’re playing these stories and the world grows.”

And nothing says that you have to follow the conventional “off to see the Wizard” storyline. If a player gets to the Munchkin village, looks around and decides to declare themselves mayor, the game will absolutely adapt the story to those new conditions. Instead of completing quests of battling flying monkeys and tipping pails of water, players will be tasked with running political campaigns and winning support from key members of the community. But again, you wouldn’t be able to walk into town, declare yourself Warlord and begin summary dissident purges — because those words aren’t in Hidden Door’s dictionary.

“We have thread templates that would be, ‘you’re persuading a bunch of people to support you in a political race,’” Mason said, “And once you are a mayor, you would be able to tell stories that just start in a different place.”

Those decisions are also persistent within the game instance. Deciding to help (or not) an NPC will impact their opinion of the player and influence their future interactions, for example. What’s more, those generated NPCs will reappear in subsequent playthroughs as recurring characters within your specific game instance.

“You can play as many stories in the same world as you want,” Mason said, “and everybody’s version of the Wizard of Oz will be really different depending on how they play over time.” NPCs and other generated assets aren’t sharable between groups yet, but that is something the team might look at implementing in the future.

In order to prevent playthroughs from getting bogged down in side quests, the Hidden Door team has developed a design philosophy that Mason refers to as “Chekhov’s Armory.” It’s basically where the system keeps track of all of the player’s in-game decisions and their influences on other assets within the story. Whenever the system needs to move the plot forward, or inject some additional drama to keep the players engaged, it can dip back into the Armory to pull out an earlier plot thread or previously wronged enemy. This also helps the system maintain continuity of the overall storyline and prevent catch-22s from forming.

“The idea was to create this feeling of the story, where your choices matter, where you have that full agency, but also there are rails moving you forward,” Mason said. “That’s been one of our most frequent design challenges, to adjust how much freedom versus how much we should motivate the story forward.”

16 secret herbs and language models

Hidden Door’s LLM differs significantly from the likes of ChatGPT in that it is not a monolithic model but rather 16 individual ML algorithms, each specialized to address a specific sub-task within the larger generative task.

We use a variety of models, some of them were building on open source models, some of them are proprietary,” Mason explained. “It’s not just one big LLM, it’s decomposing it into an interpretable system where we can use the best [AI] at the right moment.” It also enables the team to quickly plug in and benchmark newly released AI models against the existing system to see if it can improve game quality. “Frankly, we design these engines so that game designers and narrative designers can be the ones to come in and tune it, which means we have to give them those knobs”

“One big question we worked on for a while was a plot-prediction algorithm,” Mason continued. “So, ‘what should happen next based on the series of actions that is just happened?’” Interestingly the team quickly found that they could generate incredibly dull stories simply by consistently choosing the system’s top recommendation — because that choice is invariably, “the most obvious thing,” that could happen. Conversely, if the system works in too many twists and surprise reveals, the story quickly turns into chaos.

This granularity is what enables the designers to tweak the underlying game architecture to work for (example) a light-hearted Pride and Prejudice RPG as well as a grimdark Pride and Prejudice and Zombies version. “We think a lot about how our creative colleagues are going to be able to use this system to create the story experiences,” Mason said.

Gore and smooching are A-OK (but only if it’s canon)

While the game is designed to be family friendly, Hidden Door’s target demographic is the 18-35 age range and, as such, more mature themes are very much on the table top for designers, so long as they make sense within the existing story. For Wizard of Oz, violence is both ok and a major plot point.

“We work directly with authors and creators and can use as little, or as much, written material as they have,” Mason said. “We extract the characters, the types of plots, the vocabulary, the elements, the writing style, the locations.”

The team also uses what it calls a “sub-genre based model” that helps to generate the “formula” of the story. “The Wizard of Oz is largely fantasy that has a few additional rules to it, like animals can talk, but there are no dragons or other sort of fantastical creatures.” Essentially, the system takes a more general “fantasy tale” template and molds it into the specific form of the story, “down to the specific rules of the Wizard of Oz universe,” Mason said. Authors that license their works for use in the game will be able to dictate not just the initial starting plot points of the story, but the specific behaviors of NPCs and inclusion of story arcs.

There is no “Adult” story module currently available but in-game physical affection is allowed. “You can make them kiss,” Mason said. “We have a very tasteful fade to black and then you’re on to the next scene. The NPC may also reject you if they don’t like you or you don’t have the kind of relationship. That is something that’s very tunable but we try to keep it at the level of relationship in the core material.”

The future of interactive fandom

“It raises the floor for creation dramatically,” Mason said of generative AI’s broader promise to the game industry, “but it doesn’t raise the ceiling.” We’re just beginning to see gen AIs used for improving NPC dialog, Mason points out, and could be as little as a year or two away from seeing a game “fully realized” using generative AI. “The brilliance of a human with a creative vision is not something we see generally out of these systems and that is in part because of what they are: a compression of a large amount of data and an aspiration to the median.”

“I do think there’s a lot of excitement in being able to raise the floor. I think it makes creativity more accessible to a large number of people who may then decide to pursue it in their own way or use it as a tool in their process,” she continued. “I also think it makes it possible for more people to be fans of things and to have some autonomy in the way they want to interact with creativity that we don’t currently have.”

If you want to try Hidden Door for yourself, you can sign up for the waitlist ahead of future test runs.