The ‘Titan’ Tragedy’s Last 96 Hours

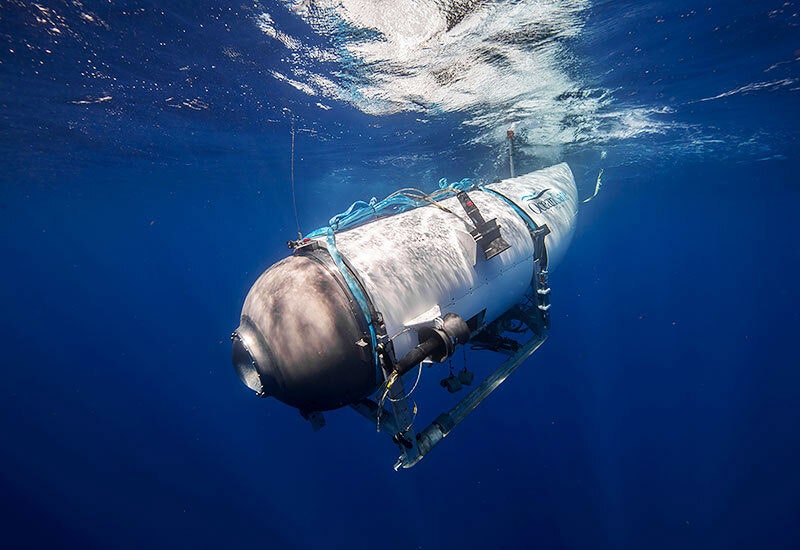

But the greatest concern was the craft’s structure. Unlike most submersibles, which have a spherical pressure hull made from steel or titanium, Titan was an experimental carbon-fiber vessel. Going dark could mean its hull had been compromised. It could mean the craft would be fragile during recovery. It could mean it had failed altogether.

With seemingly little information to work with, the search teams split their efforts between the surface and the ocean’s depths. Alongside US and Canadian authorities, commercial deep-sea firms, private vessels, military planes, and a submarine had joined the hunt by June 20. Ships and planes scoured the surface visually for signs of the sub’s white hull. Beneath the waves, rescue ships pinged the ocean with sonar in the hope of detecting the craft, with acoustics experts drafted in to analyze underwater noises.

Because of the lack of a recovery system aboard the Polar Prince, France’s sea ministry diverted its Atalante vessel—equipped with a subsea remote-operated vehicle—to assist with the operation. With its deep-diving capabilities and remote controlled cutting arms, the ROV could, if it found the sub, try to free it from any entanglements and help bring it to the surface. But for now, the Atalante was still a day away.

On June 21, the search parties confirmed they had their first lead. Rescuers divulged that surveillance vessels had detected underwater sounds at 30-minute intervals for two straight days. Periodic banging is a tactic taught to stranded submariners to assist rescue searches, and experts hypothesized that Nargeolet, formerly a diver with the French navy, would know this. “This is a search-and-rescue mission, 100 percent,” said Captain Jamie Frederick of the First Coast Guard District, dismissing the idea that the crew had already perished and that recovery of the sub was the aim. “We’ll continue to put every available asset that we have in an effort to find the Titan and the crew members.”

As the day progressed, five surface vessels were searching for Titan, with two ROVs searching in the ocean. More underwater robot vehicles were due to arrive on the morning of June 22. But they were desperately late to join the hunt. “Authorities had to airlift them to Newfoundland,” says Girguis. “They had to then place them on ships and sail them out before they could even begin searching underwater.” By the point that the underwater search of the seabed had truly gathered momentum, with the ROVs crisscrossing the ocean floor systematically to comb for the Titan, less than 12 hours of oxygen would be left on the sub.

A special naval salvage system, designed to lift up to 27 tons of machinery out of the water, also arrived in St. John’s on June 21—but it needed an additional 24 hours to be prepped for use. “We just don’t have the means to deploy a huge arsenal of rescue equipment, because it can only get there by ship, ultimately,” says Girguis. Whether the salvage system would take part in any rescue now rested on a knife edge. It was estimated that Titan would run out of oxygen at around 7 am eastern time on June 22.