Will AI revolutionize professional soccer recruitment?

Skeptics raised their eyebrows when Major League Soccer (MLS) announced plans to deploy AI-powered tools in its recruiting program starting at the tail end of this year. The MLS will be working with London-based startup ai.io, and its ‘aiScout’ app to help the league discover amateur players around the world. This unprecedented collaboration is the first time the MLS will use artificial intelligence in its previously gatekept recruiting program, forcing many soccer enthusiasts and AI fans to reckon with the question: has artificial intelligence finally entered the mainstream in the professional soccer industry?

There’s no doubt that professional sports have been primed for the potential impact of artificial intelligence. Innovations have the potential to transform the way we consume and analyze games from both an administrative and fan standpoint. For soccer specifically, there are opportunities for live game analytics, match outcome modeling, ball tracking, player recruitment, and even injury predicting — the opportunities are seemingly endless.

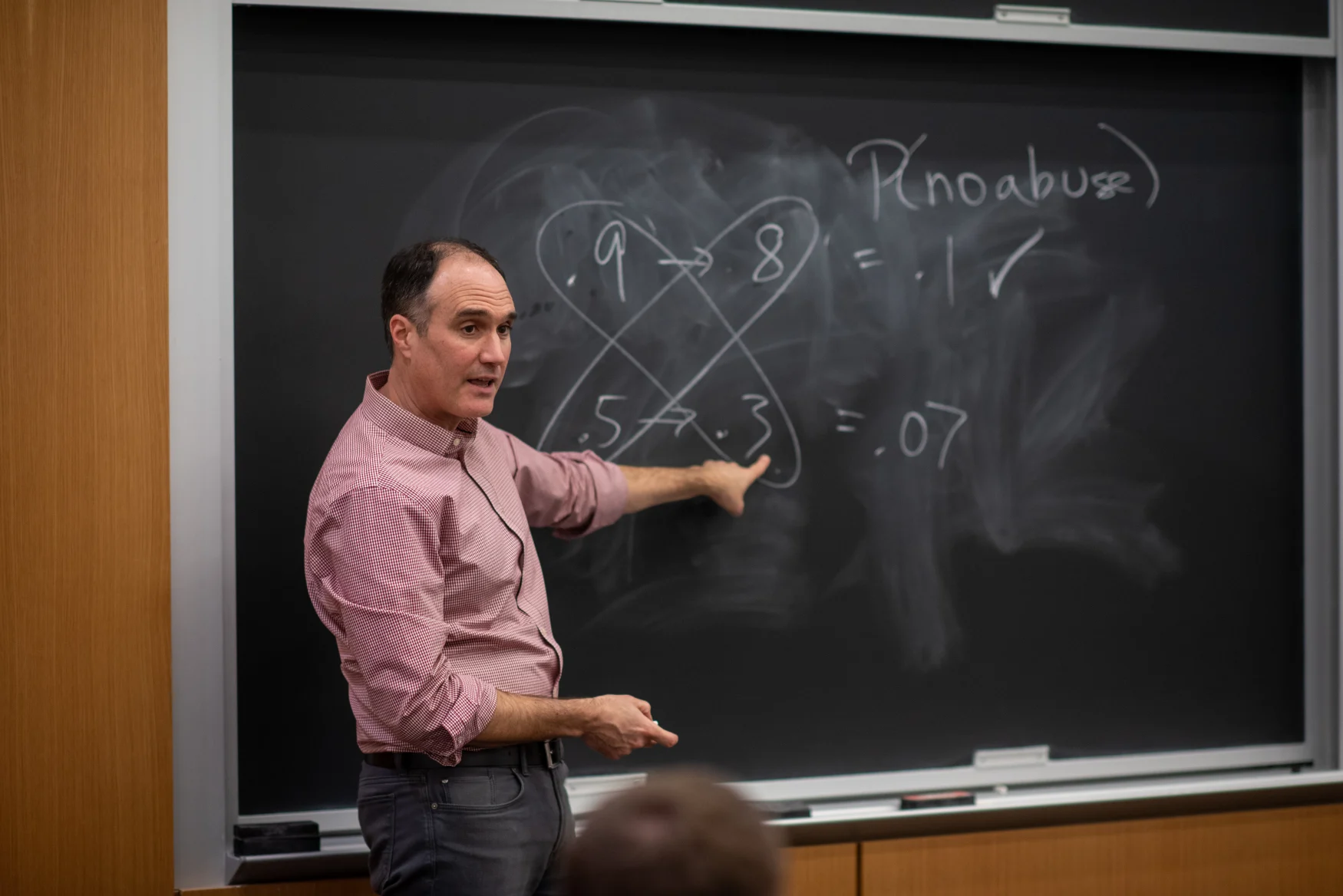

“I think that we’re at the beginning of a tremendously sophisticated use of AI and advanced analytics to understand and predict human behaviors,” Joel Shapiro, Northwestern University professor at the Kellogg School of Management said. Amid the wave, some experts believe the disruption of the professional soccer industry by AI is timely. It’s no secret that soccer is the most commonly played sport in the world. With 240 million registered players globally and billions of fans, FIFA is currently made up of 205 member associations with over 300,000 clubs, according to the Library of Congress. Just days into the 64-game tournament, FIFA officials said that the Women’s World Cup in Australia and New Zealand had already broken attendance records.

The need for more players and more talent taking on the big stage has kept college recruiting organizations like Sports Recruiting USA (SRUSA) busy. “We’ve got staff all over the world, predominantly in the US …everyone is always looking for players,” said Chris Cousins, the founder and head of operations at SRUSA. Cousins said he is personally excited about the potential impact of artificial intelligence on his company and, in fact, he is not threatened by the implementation of predictive analysis impacting SRUSA’s bottom line.

Subscribe to the Engadget Deals Newsletter

Great deals on consumer electronics delivered straight to your inbox, curated by Engadget’s editorial team. See latest

Please enter a valid email address

Please select a newsletter

By subscribing, you are agreeing to Engadget’s Terms and Privacy Policy.

“It probably will replace scouts,” he added, but at the same time, he said he believes the deployment of AI will make things more efficient. “It will basically streamline resources … which will save organizations money.” Cousins said that SRUSA has already started dabbling with AI, even if only in a modest way. It collaborated with a company called Veo that deploys drones that follow players and collect video for scouts to analyze later.

Luis Cortell, senior recruiting coach for men’s soccer for NCSA College Recruiting, is a little less bullish, but still believes AI can be an asset. “Right now, soccer involves more of a feel for the player, and an understanding of the game, and there aren’t any success metrics for college performance,” he said. “While AI won’t fully fill that gap, there is an opportunity to help provide additional context.”

At the same time, people in the industry should be wary of idealizing AI as a godsend. “People expect AI to be amazing, to not make errors or if it makes errors, it makes errors rarely,” Shapiro said. The fact is, predictive models will always make mistakes but both researchers and investors alike want to make sure that AI innovations in the space can make “fewer errors and less expensive errors” than the ones made by human beings.

But ultimately, Shapiro agrees with Cousins. He believes artificial intelligence will replace some payrolls for sure. “Might it replace talent scouts? Absolutely,” he said. However, the ultimate decision-makers of how resources are being used will probably not be replaced by AI for some time. Contrary to both perspectives, Richard Felton-Thomas, director of sports sciences and chief operating officer at ai.io, said the technology being developed and used by the MLS will not replace scouts. “[They] are super important to the mentality side, the personality side,” he said. “You’ve still got to watch humans behave in their sporting arena to really talent ID them.”

When the aiScout app launches in the coming weeks and starts being deployed by the MLS later this year, players will be able to take videos of themselves performing specific drills. Those will then be uploaded and linked to the scout version of the app, where talent recruiters working for specific teams can discover players based on whatever criteria they choose. For example, a scout could look for a goalie with a specific height and kick score. Think of it as a cross between a social media website and a search engine. Once a selection is made, a scout would determine whether or not they should go watch a player in person before making any final recruitment decisions, Felton-Thomas explained.

“The main AI actually happens less around the scoring and more around the video processing and the video tracking,” Felton-Thomas said. “Sport happens at 200 frames per second type speeds, right? So you can’t just have any old tracking model. It will not track the human fast enough.” The AI algorithms that have been developed to analyze video content can translate human movements into what makes up a player’s overall performance metrics and capabilities.

These ‘performance metrics’ can include biographical data, video highlights and club-specific benchmarks that can be made by recruiters. The company said in a statement that the platform’s AI technology is also able to score and compare the individual players’ “technical, athletic, cognitive and psychometric ability.” Additionally, the AI can generate feedback based on benchmarked ratings from the range of the club trials available. The FIFA Innovation Programme, the experimental arm of the association that tests and engages with new products that want to enter the professional soccer market, reported that ai.io’s AI-powered tools demonstrate a 97 percent accuracy level when compared to current gold standards.

Beyond the practical applications of AI-powered tools to streamline some processes at SRUSA, Cousins said that he recognizes a lot of the talent recruitment process is “very opinion based” and informed by potential bias. ai.io’s talent recruitment app, because it is accessible to any player with a smartphone, broadens the MLS’ reach to disadvantaged populations.

The larger goal is for aiScout to potentially disrupt bias by continuing to play a huge role in who gets what opportunity, or at least in the pre-screening process. Now, a scout can make the call to see a player in real life based on objective data related to how a player can perform physically. “The clubs are starting to realize we can’t just rely on someone’s opinion,” Felton-Thomas said. Of course, it’s not an end-all-be-all for bias, considering preferential humans are the ones coding the AI. There is no complete expunging of favoritism from the equation, but it is one step in the right direction.

aiScout could open doors for players from remote or disadvantaged communities that don’t necessarily have the means or opportunity to be seen by scouts in cups and tournaments. “Somebody super far in Alaska or Texas or whatever, who can’t afford to play for a big club may never get seen by the right people but with this platform there, boom. They’re going straight to the eyes of the right people,” Cousins said about ai.io’s app.

The MLS said in a statement that ai.io’s technology “eliminates barriers like cost, geography and time commitment that traditionally limit the accessibility of talent discovery programs.” Felton-Thomas said it is more important to understand that ai.io will “democratize” the recruiting process for the MLS, ensuring physical skills are the most important metric when leagues and clubs are deciding where to invest their money. “What we’re looking to do is give the clubs a higher confidence level when they’re making these decisions on who to sign and who to watch.” By implementing the AI-powered app, recruitment timelines are also expected to be cut.

Silvia Ferrari, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Cornell and Associate Dean for cross-campus engineering research, who runs the university’s ‘Laboratory for Intelligent Systems and Controls’ couldn’t agree more. AI has the potential to complement the expertise of recruiters while also helping, “eliminate the bias that sometimes coaches might have for a particular player or a particular team,” Ferrari said.

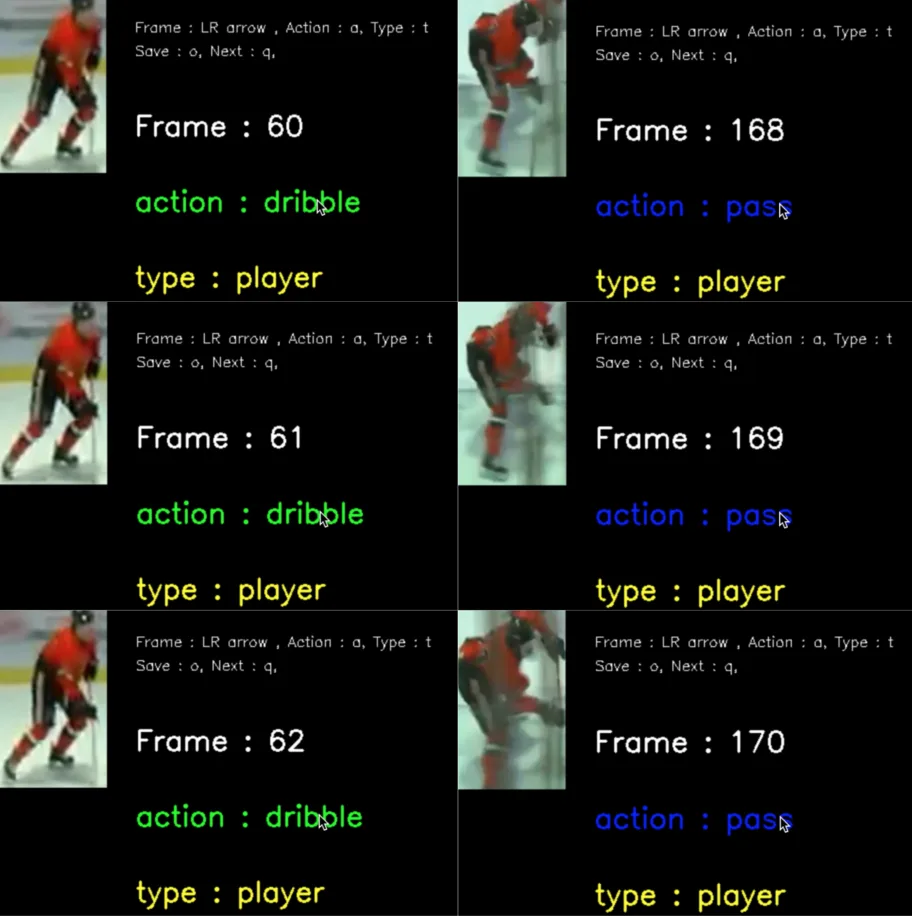

In a similar vein, algorithms developed in Ferrari’s lab can accurately predict the in-game actions of volleyball players with more than 80% accuracy. Now the lab, which has been working on AI-powered predictive tools for the past three years, is collaborating with Cornell’s Big Red men’s ice hockey team to expand the project’s applications. Ferrari and her team have trained the algorithm to extract data from videos of games and then use that to make predictions about game stats and player performance when shown a new set of data.

“I think what we’re doing is, like, very easily applicable to soccer,” Ferrari said. She said the only reason her lab is not focused on soccer is because the fields are so large that her team’s cameras could not always deliver easily analyzed recordings. There is also the struggle with predicting trajectory and tracking the players, she explained. However, she said in hockey, the challenges are similar enough, but because there are fewer players and the fields are smaller, so the variables are more manageable to tackle.

While the focus at Ferrari’s lab may not be soccer, she is convinced that research in the predictive AI space has made it “so much more promising to develop AI in sports and made the progress much faster.” The algorithms developed by Ferrari’s lab have been able to help teams analyze different strategies and therefore help coaches identify the strengths and weaknesses of particular players and opponents. “I think we’re making very fast progress,” Ferrari said.

The next areas Ferrari plans to try to apply her lab’s research to include scuba diving and skydiving. However, Ferrari admits there are some technical barriers that need to be overcome by researchers. “The current challenge is real-time analytics,” she said. A lot of that challenge is based on the fact that the technology is only capable of making predictions based on historical data. Meaning, if there is a shortage of historical data, there is a limit to what the tech can predict. Beyond technical limitations, Felton-Thomas said implementing AI in the real world is expensive and without the right partnerships, like the ones made with Intel and AWS, it would not have been possible fiscally.

Felton-Thomas said ai.io anticipates “tens of millions of users over the next couple of years.” And the company attributes that expected growth to partnerships with the right clubs, like Chelsea FC and Burnley FC in the UK, and the MLS in the United States. And while aiScout was initially designed for soccer, the company claims that its core functionalities can be adapted for use in other sports.

But despite ai.io’s projections for growth and all the buzz around AI, the technology is still a long way from being widely trusted. From a technology standpoint, Ferrari said “there’s still a lot of work to be done” and a lot of the need for improvement is not just based on problems with feeding algorithms historical data. Predictive models need to be smart enough to adapt to the ever-changing variables in the current. On top of that, public skepticism of artificial intelligence is still rampant in the mainstream, let alone in soccer.

“If the sport changes a little bit, if the way in which players are used changes a little bit, if treatment plans for mid-career athletes change, whatever it is, all of a sudden, our predictions are less likely to be good,” Shapiro said. But he’s confident that the current models will prove valuable and informative. At least for a little while.