The Man Who Trapped Us in Databases

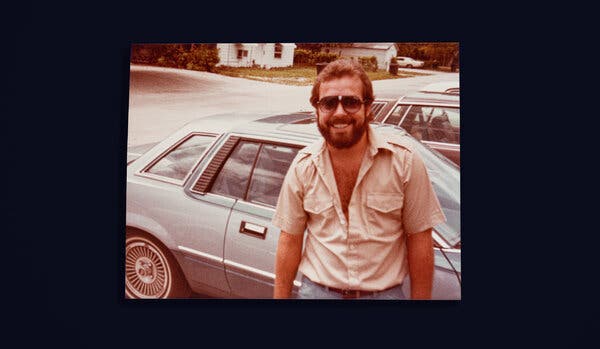

One Saturday night a decade ago in South Florida, hundreds of mourners filed into the Boca Raton Resort & Club, a pink palazzo relic of the Roaring ’20s, and settled at tables in its Grand Ballroom. The dress code for the evening was “Hank casual,” and the mood, in keeping with the man being honored, was surprisingly exuberant. “Hank” was Hank Asher, the multimillionaire king of the data brokers, and the event marked not so much the death of a man as the birth of a ghost.

In pages of tributes to Asher on his website and in The Palm Beach Post — as well in as conversations with me over the years that followed, as I became more obsessed with him and his career — friends couldn’t stop marveling at his charm, his daring, his generosity, his volatility, his partying, his sleeplessness, his middle-of-the-night phone calls, his thousand-yard stares, his maddening disdain for social niceties and his superhuman, almost computerlike ability to take in information and discern patterns. He was also described as turbulent, sometimes violent, not always right in the head. You never knew what he would do next, so you couldn’t turn away.

One acquaintance called it “the Hank show.” Asher was its star, but his performance had, over time, widened to friends and colleagues and customers and accomplices and, ultimately, to everyone, everywhere. He was one of the first and best data miners of the digital age: a person who built his own reality, then sucked the rest of the world in. He had made his first fortune painting South Florida’s growing forest of condo towers, and his second as a drug runner feeding its growing appetite for cocaine. He spent years in the cross hairs of the D.E.A. and the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, and yet a decade after his death, his data and database products still course through the computer systems of the F.B.I., the I.R.S. and ICE; through 80 percent of the companies in the Fortune 500; through nine of the world’s 10 biggest banks; and through a good part of America’s roughly 18,000 law-enforcement agencies. Our world — and my world, as a reporter seeking data — runs on what he built, even if, a decade on, the man himself has largely been forgotten. He’s the ghost in our machines.

In the ballroom that night, Asher’s longtime lawyer, one of his many lawyers, called him an unsung legal genius. A doctor from the Mayo Clinic — where Asher was a major donor — explained how he helped fund novel strategies against cancer. John Walsh, the host of “America’s Most Wanted” and a good friend, described how Asher flew harrowing rescue missions to Haiti after the 2010 earthquake and had for years given free software and many millions of dollars to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Colleagues remembered Asher’s usual business attire: shorts, deck shoes, pink shirt, aviator sunglasses. An early employee recalled Asher’s first words to him in an elevator in Pompano Beach, Fla., in the 1990s: “Who the [expletive] are you?”

Asher would ask that question of many people, first face to face, and then — as the technology advanced, and his understanding of its power advanced with it — by way of data systems. Soon enough, he could find out who you were without asking. I first heard about Asher a few years after his death. A magazine editor called with a potential assignment, about a campaign against child trafficking in Central America. When I researched it, I read that the group leading the effort had partnered with a “data-mining software company” in Florida. I didn’t end up taking the assignment, but at some point I looked up the company, then looked up its founder. The more I read about him, the better I understood that he would have — could have, with a flutter of his thick fingers — known everything about me.

One of Asher’s innovations — or more precisely one of his companies’ innovations — was what is now known as the LexID. My LexID, I learned, is 000874529875. This unique string of digits is a kind of shadow Social Security number, one of many such “persistent identifiers,” as they are called, that have been issued not by the government but by data companies like Acxiom, Oracle, Thomson Reuters, TransUnion — or, in this case, LexisNexis.

My LexID was created sometime in the early 2000s in Asher’s computer room in South Florida, as many still are, and without my consent it began quietly stalking me. One early data point on me would have been my name; another, my parents’ address in Oregon. From my birth certificate or my driver’s license or my teenage fishing license — and from the fact that the three confirmed one another — it could get my sex and my date of birth. At the time, it would have been able to collect the address of the college I attended, Swarthmore, which was small and expensive, and it would have found my first full-time employer, the National Geographic Society, quickly amassing more than enough data to let someone — back then, a human someone — infer quite a bit more about me and my future prospects.

When I opened my first credit card, it got information from that; when I rented an apartment in New York City, it got information from that; when I bought a cheap car and drove across the country, it got information from that; when I got a speeding ticket, it got that; and when I secured a mortgage and bought my first house in Seattle, it got that.

Two decades after its creation, my LexID and its equivalents in the marketing world have connected tens of thousands of data points to me. They reveal that I stay up late and that I like to bicycle and that my grandparents are all dead and that I’ve underperformed my earning potential and that I’m not very active on social media and that I now have a wife and kids, who, if they don’t already have LexIDs, soon will.

Persistent identifiers let algorithms map in milliseconds a network of people I’ve met, lived near or interacted with online or off, and they show the trajectory of my life — up, down and sideways. They help health systems assess my living conditions, impacting what kind of care I get from my doctor. They affect how much I pay for car insurance. They help determine what kind of credit cards I have. They influence what ads I see and how long I wait on hold when I call a customer-service line. They allow computers inside police departments, intelligence agencies, hospitals, banks, insurance companies, political parties and marketing firms to understand personal behavior and, increasingly, as artificial intelligence and machine learning expand into every corner of society, to predict and exploit it.

This has been going on for longer than we realize. Asher’s first data start-up, Database Technologies, created a system that Florida authorities used to purge tens of thousands of voters, most of them Democratic, many of them Black, from the state’s 2000 election rolls, helping put George W. Bush over the top in his effort to take the White House. He had already left the company by that point and started his next, Seisint, which worked with the Bush administration to build Matrix, a controversial post-Sept. 11 surveillance program. The program died in 2005, but the technology lived on in evolving forms inside the C.I.A. and other federal and state agencies. As I dug deeper, I learned that divisions of the information giants LexisNexis, Thomson Reuters and TransUnion descended from data businesses Asher founded. The work of their clients — police departments, government agencies, much of corporate America — is propelled by his legacy.

Remembered by industry insiders as the “father of data fusion,” Asher reigned over a vast shift in privacy norms. He shifted them himself, scooping up data sets no one else had wanted, monetizing information no one had ever thought valuable, collecting details others had thought too intimate, testing boundaries that more established companies — with their brand names and boards and reputational risks and publicly traded stocks — had yet to ever dare test.

Why him? One answer is that Asher had a mind for this stuff. He scanned volumes of information too enormous for most humans to take in, finding secrets in the data that most humans would never recognize. A computer scientist who helped build Matrix told me that his former boss could look at a mass of numbers on a whiteboard and see immediately what others could not, picking out patterns in seconds. Artificial intelligence hadn’t really been part of Matrix, the executive said, not back then: “That was still Hank. Hank was the algorithm.” But that’s only one answer as to why him.

Another answer, the better one, is that Hank Asher never cared about norms.

One thing that gave Asher his edge was his criminal past. His first known drug run, in 1981, was a load of pot from northern Belize. There was a dense fog on the predawn morning he was meant to take off, and his plane, a sleek twin-engine Aerostar, was packed dangerously full. The airstrip was dangerously short. Worried they would be spotted as the day broke, he and a smuggling partner wheeled the plane to the adjacent highway, and Asher used it as his runway, lifting off before a rumbling convoy of sugar trucks could block his path.

He flew north over the Yucatán Peninsula and low over the Gulf of Mexico to an airstrip in rural Oklahoma, helped a waiting crew unload and returned to Belize the same day, euphoric, hugging his fellow smuggler and kissing him on the cheek. Asher had instantaneously wiped a $60,000 debt clean. But there was more to it. He was happiest whenever there was something — danger, conflict, sex, logistical puzzles, psychotropic drugs — to wholly occupy his hyperactive mind. Smuggling had been just his kind of rush. He was hooked.

Belize had plenty of weed, but it also had a strategic location. It was right between the cocaine growers in South America and the users in the United States. On a previous scouting trip to the newly independent country, Asher discovered Caye Chapel, a tiny, pancake-flat, rarely visited island near the barrier reef that featured a 3,600-foot stone airstrip, so solid and grippy that it could have been asphalt. He saw right away that it could help solve one of the cocaine trade’s inherent bottlenecks: Try to fly a heavy load up from Colombia nonstop in a small plane, and you would run out of fuel before you got anywhere north of Central Florida. Carry more fuel, and you couldn’t carry a full payload of drugs. Get a bigger plane, and you would need bigger, less private runways.

Asher and his smuggling partner bought a two-room bungalow on Caye Chapel. It became their refueling station. “What Hank would do,” the partner told me, “is go down in the Aerostar, fuel up at Belize City and go out to the cay, where we would defuel the Aerostar and transfer it to my plane — his Aerostar was our flying fuel tank.” At least once, Asher provided cover by vacationing on the island with one of his girlfriends and their 2-year-old daughter, the partner remembers — just a family man on a family trip.

In time, as he proved himself and forged his own cartel connections, his Aerostar was filled not just with fuel but with bricks of cocaine. He flew the cocaine to a remote ranch in Florida’s Okeechobee County, unloaded with the props still spinning and took off again, celebrating his runs with a signature move — a barrel roll — as he flew away.

On many of Asher’s increasingly frequent trips through the Caribbean, he was joined by another one of his girlfriends, a young woman named Marci Tickle. She was a secretary at the Asher Waterproof Coatings, Roofing and Painting Corporation, the condo-painting empire Asher had built over the previous decade, the largest in South Florida. She understood their trips to be vacations, but strange things kept happening: a crash-landing in the Bahamas, a landing in Guatemala City surrounded by gunmen, a pair of military jets out her window one day as they re-entered U.S. airspace, which she remembers Asher easily ditching because somehow he knew to fly low and slow.

One day he bought Tickle a round-trip ticket to Tallahassee and gave her a bag of gold coins, South African Krugerrands, to deliver to an associate. He said it had to do with the painting business. “I remember specifically that they were $425 an ounce,” she told me.

Already impulsive, he became erratic. In 1982, he abruptly sold the painting company to “a group of South Africans, a couple New Yorkers that I do not really remember,” as he later explained in a deposition, getting only the $600,000 down payment on what was supposed to be $3 million. He suggested to Tickle that they marry — but kept dating other women. He moved from his longtime home, Fort Lauderdale, to the Bahamas, to the island of Great Harbour Cay. He told people he was retired.

He still visited Florida, but now he came and went quietly, with little notice. He often showed up unannounced at Tickle’s apartment, and he used her bedroom to hide heavy bundles of $20 bills, which were wrapped in paper bags and took up much of her closet space. One night, he told her he had to go out for a bit, then simply disappeared — gone for days. Tickle was livid when he finally returned, certain he was cheating on her again. He screamed back at her. He said he had been in Colombia. “I’ve been hiding out in the jungle!” he thundered. “I’ve been sleeping with pigs!”

One of the times she visited him on Great Harbour Cay, he was strung out on cocaine, alone in his beachfront home, crying. He begged her not to break up with him. They soon did anyway.

Asher sent Tickle a letter at the end of 1983, and she held on to it for decades as their lives diverged. He wrote that he had become close with a neighboring property owner on the island, a lawyer. Change was coming, something very different. The lawyer was F. Lee Bailey, who made headlines as the counsel for Patty Hearst and other celebrity defendants. (He would later go on to join the “dream team” defending O.J. Simpson.) “Things or (tingums) as they say here are going so good,” Asher wrote. “F. Lee is really a nice guy and has taken a real liking to me. He has dinner with me almost every night he is here.”

Asher was done with smuggling. He wanted to bury that in the past. His friend Lee had brought not just the view from the other side of the law but a magical new piece of technology, and Asher was in awe of its budding power. Once again, he was getting hooked on something, an obsession that would change his life, and eventually all our lives: “I’m learning how to run a computer!”

By 1986, Asher was back in South Florida, the specter of prison time now behind him: Bailey had helped him become a D.E.A. informant, and for his federal handlers Asher produced lists of smugglers’ names, identified boats and provided other details of the trade.

One afternoon, wearing a Panama hat and an unbuttoned shirt, he marched into the drab offices of the CPT Corporation, a technology company in Hollywood, and talked his way past the receptionist. “Can you sell me a computer?” he asked the surprised men in the back office. Selling computers to individuals wasn’t their business — they sold computers to law firms — but they decided they could do it in his case.

One of the men, a black-clad, self-described “half-assed anarchist” named Roy Brubaker, agreed to show Asher how to use it. They began meeting weekly, soon even more frequently, teacher and student sitting side by side in front of their laptops at a table in Asher’s plain two-bedroom house in Hollywood or by the water on Great Harbour Cay — or, once, in the glass-walled conference room at Bailey’s law office in Palm Beach. Asher’s computer was a Toshiba T1100, one of the world’s first mass-market laptops, equipped with a nine-inch black-and-white screen and a 4.77 MHz processor, roughly 700 times slower than the biggest processor in a modern iPhone. He quickly mastered the spreadsheet program Lotus 1-2-3, so Brubaker taught him the database program R:BASE, and Asher mastered that right away, too. He often got so deep into coding that Brubaker went home to sleep and returned the next day to find him still hunched over the Toshiba. “Hank could never disassociate himself from a problem,” he said. “He couldn’t come back and look at it. He hung on to it like a pit bull until he could come up with some kind of solution.”

After a few months, Asher had become a real coder, and he and Brubaker decided to go into the programming business together. The most enduring of the three companies they founded would be Database Technologies, incorporated on Feb. 18, 1992. The partners rented a two-room office in a former medical building on a busy four-lane road in Pompano Beach, north of Fort Lauderdale. They hired a secretary, and soon after, Brubaker recalled, Asher was sleeping with her.

At first, Asher and Brubaker took whatever programming jobs they could get. They built a server for a hotel chain, inventory-management software for a maritime-parts dealer, a database for a rent-to-own furniture company and an order-fulfillment platform for a corporation that sold fruit baskets over the phone to customers around the country.

Then one day, about six months in, Asher heard from a mutual friend about a guy in Tallahassee who needed help with public records — something about motor vehicles, something about a big database.

The man, John LeGette, was a tall former hippie who spent his time chasing down D.M.V. records on behalf of auto-insurance companies. In their first phone call, LeGette explained that he wanted to take the entire vehicle-registration database of the Florida Department of Highway Safety and make it searchable by address.

“I can do that,” Asher said.

“There are 26 million records.”

“That is no problem.”

“Well, son,” LeGette said, “we are going to make a lot of money.”

Until now, Florida’s nascent insurance-data industry had revolved around files known as motor-vehicle records, or M.V.R.s — which, despite the name, were concerned with drivers, not vehicles. The M.V.R. was the state’s official ledger of a license holder’s past accidents and traffic tickets. It was one of the earliest means by which an automotive insurer could assess an individual as an individual, moving past the broad categories of risk — a person’s age, gender, type of car — that otherwise determined premiums.

To get an M.V.R., which was a public record, you could show up at the Department of Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles headquarters, pay two dollars to a clerk and wait for someone to go pull it off the mainframe. But in practice, most insurance companies got these files via middlemen like LeGette or via runners working for his major competitor, Equifax, the oldest of the “big three” credit bureaus. The middlemen picked up the product in Tallahassee and sent it to the booming insurance market down in South Florida, 400 miles away, where most of the drivers were. Geographically, it was like the cocaine trade in reverse.

LeGette made an easy six figures a year brokering M.V.R.s. What had taken him to Asher was the lure of an even greater treasure, one hiding in plain sight: the Department of Highway Safety’s trove of vehicle registrations, an untapped resource held separately from M.V.R.s. These the department sold for a penny a record, a low price (relative to those $2 M.V.R.s) that reflected their perceived lack of value: Whereas a single M.V.R. file was useful by itself — it tells you something when a guy has a dozen moving violations on his record — a single vehicle registration offered only a car owner’s name and address.

But LeGette was early to the insight that some data, however worthless in isolation, could be extremely valuable in aggregate. Layer vehicle-registration records upon one another in a database, and you could see who shared an address, who shared a name, who lived together, who was most likely related to whom — and who, under Florida’s relatively new no-fault car-insurance laws, might also be on the hook for any claims in the event of an accident. “Let’s say that you and your wife both have a car,” LeGette recalled explaining to Asher, “but you’re insured with Company A and she’s insured with Company B. Because of the way the law is written, both policies are on that loss.” A computer system that allowed insurers to look up vehicles by shared address — which allowed them to cut some claims payouts in half — would be worth millions.

On the phone, Asher grasped the idea’s potential immediately. Everyone was hiding something — he knew he had been ever since that first drug run in Belize — and LeGette was sketching out an ingenious plan to use data to reveal hidden relationships. Asher soon jumped to another industry that might find such a database useful: law enforcement.

When he explained his thinking to Brubaker, a “small l” libertarian and nascent Buddhist, his partner recoiled. “One of the steps on a full path is: Don’t have an occupation that causes harm,” Brubaker told me. “I was having a hard time reconciling that with a database that would be able to track anybody down.” He feared what would happen if they layered on more data, what would happen if cops and federal agents could just peer into your life — where you lived, who you knew — without a warrant. Brubaker’s father and grandfather were Miami police officers. “I’ve always been concerned about the reach of government,” he said. “Offering this to police departments, I just saw a vast potential shitstorm for us average folks.”

Asher wouldn’t drop it. He set up a meeting with his old D.E.A. handler, surprising the agent with a question as they sat in an unmarked car on the apron of a small airport near Miami: “If I could give the agency instant access to public records, how much would that be worth?”

Asher forced Brubaker out of their company, and he has lived paycheck to paycheck ever since. “But I walked away with my soul,” he said.

It took a certain kind of mind to envision the systems Asher now wanted to build, but it also took a certain mentality. What would separate his databases from most of their contemporaries would be not just the records they held or the technology they employed but their focus on what is today blandly known in the industry as “risk.” They would be designed to manage risk for insurers, and eventually for society writ large, by uncovering what a person might intentionally or unintentionally be hiding: an asset, an associate, an address, a conspiracy, a conviction and so on.

Such risk analytics are predicated on mistrust, so it was no surprise that Asher, with his own big secret to hide and difficulty trusting anyone, would become a pioneer in the space. Contrast his creations with, say, a marketing database from the same era, focused on what brand of shampoo or model of car a person has bought in the past or might be swayed to buy in the future, and the questions asked and answered were very different. Instead of asking, “What will this person like, and what will he buy?” it asked, “What isn’t he telling us, and what will he do wrong?” Asher, in taking on LeGette’s database project, had started encoding a certain paranoia — his own — into American life.

“Is this the meanest lawyer in Tallahassee?” the gruff voice asked. It was 5 a.m., and Martha Barnett was on her way to the airport. She had stopped by her law office only because she accidentally left her paper ticket there (it was the early 1990s), but then the phone on her desk — her direct line — started ringing. She didn’t recognize the voice. Thinking it a prank call, she hung up.

The phone rang again as she was walking out the door. “I’m trying to find Martha Barnett,” the man continued. “I’ve heard she’s the meanest lawyer in Tallahassee.”

“I’m Martha Barnett,” she said. “And who are you?”

“Well, I need a lawyer,” he explained.

“What do you need a lawyer for?” she asked.

She thought she heard him say he needed a copy of his driver’s license. “You don’t need a lawyer for that,” Barnett told him. “It’s a public record. You just call the Department of Highway Safety.” No, he said, he wanted all of them. But the state wouldn’t give them to him.

“How many licenses do you have?” she asked.

No, he explained, he wanted everyone’s — every driver’s license in Florida.

“Now I can see why you might be having a problem,” Barnett replied.

She finally got the man’s name: Hank Asher. She promised she would call him back.

In her follow-up call, Barnett, a future president of the American Bar Association and the first female partner at Holland & Knight, one of Florida’s top law firms, asked Asher to explain why he wanted driver’s licenses. He described the machine he was building, some kind of public-records database for insurance companies and cops. “You know, I truly don’t understand what you’re doing,” Barnett recalled responding. “Maybe if I came to your facility, I’d better understand it.”

Asher picked her up at an airport in Palm Beach a day or two later. They sped south to Pompano and parked outside the unimpressive Database Technologies building, and Asher proudly walked Barnett upstairs and into the computer room. With Brubaker, he’d had a breakthrough idea to build supercomputers by stringing together dozens of consumer-grade P.C. processors in “massively parallel” systems that split big jobs into tiny pieces, a processor for every data point, a virtual eyeball on every pixel. “It’s kind of like teaching a thousand chickens to pull a wagon,” Asher once told Vanity Fair.

Barnett thought to herself that it looked like the computers were all sitting on bread racks. This, Asher told her, is where they would store all the data from the driver’s licenses if they could get them, where they would try to layer data set upon data set upon data set, fusing it all into one.

Asher started to explain again why he was collecting public records, but it didn’t click until he handed Barnett a newspaper clipping. It was about a child abduction in South Florida, a little girl who was grabbed in a parking lot. Witnesses saw it happen, but the details were murky. “They knew that she got into a dark car, either a navy blue or black car,” Barnett said. “They got part of the license tag but didn’t get the whole tag.”

Police detectives had come to Asher for help, and as they told him what they knew over the phone, he typed the fragments into his computer. His database, still young, was already a living, multidimensional thing compared with the static rolls of magnetic tape that LeGette had been delivering from Tallahassee. The vehicle registrations had been “keyed”: Each data field — plate number, VIN, make, model, color, year, owner’s last name, owner’s first name, owner’s street address — was now indexed and individually searchable.

Asher’s query, the few numbers of the license plate and the car’s color — black or blue — shot over to the computer racks, crawled through the indexes and came back, and a list of potential suspects appeared on his monitor. He read the names and addresses back to the cops. The perpetrator, it would turn out, was on the list, and within an hour, Barnett recalled, the man was in custody, the child safely returned to her family.

“I was just blown away,” Barnett said. “I sat there, and I went: ‘Oh, my God. Oh, my God.’” She soon signed on to represent Database Technologies. With her on board — and with Florida’s open-government laws in favor of those seeking public records — the dam burst. Asher and LeGette got Florida’s driver’s licenses, millions of them, and immediately began seeking out other data sources, including corporate records from the Florida Department of State. For Asher, “it was all about the amount of data you have,” LeGette said. “The more you have, the more you have.”

Years later, in a deposition for a trade-secrets case against a would-be competitor, Asher detailed his database’s explosive growth. A lawyer asked if he could pinpoint when Database Technologies bought various categories of data.

“Probably,” Asher answered.

“Let’s go through them. As to the vehicles, do you know when — ”

“ ’92.”

“Driver’s licenses?”

“ ’93.”

“Corporate records?”

“ ’93.”

“Professional licenses?”

“ ’93.”

“Marriage and divorce records?”

“ ’95, I think.”

“More or less?”

“All of these are more or less.”

“Handicap stickers?”

“June 18, 1994. I am kidding. It is ’94.”

“Property-ownership records?”

“Probably ’94.”

Later, the lawyer asked, “Would you say that government agencies, because they disclose public-record databases, can be considered a competitor?”

“That is an abstract question, and it would have an abstract answer,” Asher replied. “I do not think they are a competitor. I don’t know that ‘competitor’ is the right word.”

In fact, government agencies were in some ways enablers of brokers like Asher, often unwittingly. It would take years for states to catch up and start imposing limits. “People were giving this data away,” Barnett said.

Two years after its founding, Database Technologies housed two terabytes of data — the equivalent of hundreds of billions of words. A year later, that amount had doubled. The company expanded its information-gathering operation to other states and bought up smaller and niche brokers and their data, leased corporate records from Dun & Bradstreet and obtained addresses and listed and unlisted phone numbers from TransUnion and eventually Equifax and Experian. Its data troves doubled in size again, then again, then again. It was becoming next to impossible to hide from Asher’s machine.

It was also becoming next to impossible for Wall Street to ignore what Asher had built. One rainy afternoon in Pompano Beach, Ken Langone — a founder of Home Depot and a future director of the New York Stock Exchange — strode into Asher’s office for a surprise visit. Within weeks, Database Technologies was on its way to going public. Its executives pitched or took investments from a bipartisan array of plutocrats: Donald Trump, George Soros, Stanley Druckenmiller and Langone himself. By September 1996, Hank Asher was worth more than $100 million.

In 1998, as rumors swirled about Asher’s past as a smuggler — and after Langone, fed up with his erratic management of the company, helped engineer his ouster from Database Technologies — he used his fortune to start a new data-fusion company, eventually called Seisint, that would go head-to-head in competition with his old one. He soon had far faster computers and, thanks to the explosion of the internet, vastly more data. He was still in Florida. So when hijackers from Al Qaeda who had lived in his state flew jetliners into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on Sept. 11, 2001, and when all of American law enforcement urgently wanted to know who they were and what they wanted and who else might be out there, Asher found himself at the center of history.

“I haven’t slept since the planes went into the towers,” he told Barnett by phone the next day. He and his staff had been contacting every law-enforcement agency they could, offering free access to his latest database product. The evening of Sept. 13, Asher stood with Bill Shrewsbury, a former D.E.A. investigator and agent with the Florida Department of Law Enforcement who had become his right-hand man, in Asher’s 9,500-square-foot house in a gated community in Boca Raton. Asher had a giant martini in one hand, Shrewsbury recalled, and at one point he stopped talking and just stared into space.

“I can find these [expletives],” Asher suddenly declared. “I can find every last one.” He ran toward his master bedroom and sat down in front of a keyboard. “Give me a name,” he told Shrewsbury. “Give me a Muslim name.”

“Uh, Mohammed?” Shrewsbury offered.

“That’ll do,” Asher said.

It was 8 p.m. He tapped into Seisint’s database and began parsing billions of records he had collected: motor-vehicle and court records like those his former company had always held, but now also email addresses and mailing-list files and credit-agency data. He hunted for people with the characteristics — Muslim, male, young, new arrival to America and so on — that he believed fit the profile of a terrorist.

“Within 30 seconds,” he later told the journalist Robert O’Harrow, “I had 32,000 people up of interest.” Now he needed to refine the list, and he began to write the code to do so, looking for connections between the names: a shared address, a shared phone number, a common date that they first showed up in the records.

Shrewsbury hovered for a couple hours, watching Asher think, then type, a human algorithm at work, before going to bed in the guesthouse. Asher was still at it when he called Shrewsbury at 6:30 the next morning. He was calculating nearly every adult American resident’s likelihood of being a terrorist, a score that he would eventually call the “terrorism quotient” or the “H.T.F.,” for High Terrorist Factor. That afternoon, Asher gave his first version of the list to the F.B.I. and the Department of Justice, then to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. The list had 419 names. One was Marwan al-Shehhi, the man piloting the plane that flew into the south tower.

Asher soon incorporated UPS data and Equifax credit records into the High Terrorist Factor. He saw who opened credit cards on the same day using the same address, who sent packages, who received them, who lived together and who lived together twice. After pulling in more data, including Florida law-enforcement records, he refined the model further, programming it to weigh such factors as a person’s race, criminal history and physical proximity to the addresses of known terrorists. The system spun more names for delivery to law enforcement — eventually 120,000 names, including a “1 percent list” of 1,200 mostly Muslim men with the highest scores.

Five of the 1,200 people on the list, including al-Shehhi, were Sept. 11 hijackers. Fifteen were already targets of active federal investigations. Dozens more were previously unknown to the authorities — and were soon detained for immigration violations. At the time, Muslim men were being scrutinized and jailed all over the nation.

Matrix, as Asher’s new counterterrorism system soon came to be known, arguably marked the beginning of our era of analytics. Your risk, scored. Your data as prediction, not just description. While marketers had long rated prospects, and while Fair, Isaac and Company credit scores — FICO scores — were decades old, now actuarial science was jumping the rails to predict other aspects of a person’s character. By all appearances, the refined H.T.F. algorithm got more than 1,000 innocent men wrong, an extraordinarily high false-positive rate. But Asher, enamored with the power of his magical machines, kept talking about the five names they got right.

Many critiques of our increasingly algorithmic world focus on where algorithms fail. One boils down to simple math: Some sample sizes are so small (of terror attacks, for instance) that algorithms can hardly reliably predict what they purport to predict. Another boils down to psychology: As anyone who has ever become lost by blindly following Google Maps can attest, people tend to perilously ignore common sense and trust the machine. A third boils down to checks and balances: Algorithms are often proprietary black boxes, closed to outside scrutiny. A fourth critique points out that algorithms, far from being objective, often just encode and scale up human biases: If a predictive policing system learns that most of a city’s arrests have historically been in a certain majority-Black neighborhood, the computer may decide to deploy more officers to that neighborhood, perpetuating a racist pattern of arrests and violence. Garbage in, garbage out.

But the story of Hank Asher and his creations also raises a different question, one ever more pertinent as the science and machinery of A.I. march continually forward: What happens when this stuff actually works? Is that better or worse?

A world in which computers accurately collect and remember and increasingly make decisions based on every little thing you have ever done is a world in which your past is ever more determinant of your future. It’s a world tailored to who you have been and not who you plan to be, one that could perpetuate the lopsided structures we have, not promote those we want. It’s a world in which lenders and insurers charge you more if you’re poor or Black and less if you’re rich or white, and one in which advertisers and political campaigners know exactly how to press your buttons by serving ads meant just for you. It’s a more perfect feedback loop, a lifelong echo chamber, a life-size version of the Facebook News Feed. And insofar as it cripples social mobility because you’re stuck in your own pattern, it could further hasten the end of the American dream. What may be scariest is not when the machines are wrong about you — but when they’re right.

When Asher died, alone at home at age 61, on Jan. 11, 2013, he was in the midst of trying to build a third data company: He had been pushed aside at his second company, Seisint, much as he had been forced out of his first, because of his increasingly chaotic behavior and after his history as a smuggler came to light. He was burning through more than a million dollars a week on operations and a state-of-the-art computer room just down the way from his old computer room. He was burning through millions more buying up vast data sets that contained ever more granular information on Americans’ lives.

The cause of death, more prevalent among the obese and those who sit in front of computer monitors for manic days on end, was bilateral pulmonary embolism.

In a safe deposit box, Asher’s younger daughter would soon find a hoard of silver coins and two gold Krugerrands: a drug smuggler’s currency, spoils of the past that he could never really shake. The executor of Asher’s estate would find that his fortune, once hundreds of millions of dollars, had dwindled to less than a million dollars’ worth of jewelry, cars and other small assets, his stake in his last start-up — TLO, for The Last One — and $725,349 in cash. But his legacy was far more than his fortune. His machines, still spinning, still targeting, still scoring, still expanding into new facets of the human experience, would forever be.

McKenzie Funk is a ProPublica reporter in Washington State and the author of the new book “The Hank Show.” His last article for the magazine was about how U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement finds its targets in the surveillance age. Erik Carter is a graphic designer and an art director in New York. His work often plays off an internet aesthetic and mixes media.

Source photograph for top image: Eliot J. Schechter/Bloomberg, via Getty Images.