At Last, ‘Ugly’ Sea Lampreys Are Getting Some Respect

Writing in the May 2022 issue of Estuary magazine, Gephard and his colleague, fisheries consultant Sally Harold, reported what they observed while snorkeling downstream of a communal lamprey nest: “An entire school of spottail shiners is lingering, intimidated by our presence and gobbling any errant eggs that are swept past the gravel mound. Dozens of common shiners, the males displaying vivid flashes of orange on their fins, are darting in and out of the nest, snatching the tiny eggs before they sink to the bottom. Even when an egg falls amongst the gravel, it may not be safe. As we watch, the heads of small American eels—elvers—protrude from the gravel in search of eggs. A typical lamprey female will produce around 200,000 eggs, so there are enough to share.”

In the Connecticut River’s main stem, Gephard sees the carcasses of spawned-out lampreys seething with feeding caddisfly larvae, prime forage for birds and dozens of fish species.

Sean Ledwin, director of Maine’s Bureau of Sea Run Fish and Habitat, used to work on Pacific lampreys. To illustrate the difference in western and eastern perceptions, he tells the story of his outreach efforts. “In Maine,” he says, “people are horrified when we show them sea lampreys. In California we displayed a Pacific lamprey in a tank, and a kid from Hoopa tribe said, ‘That looks delicious.’”

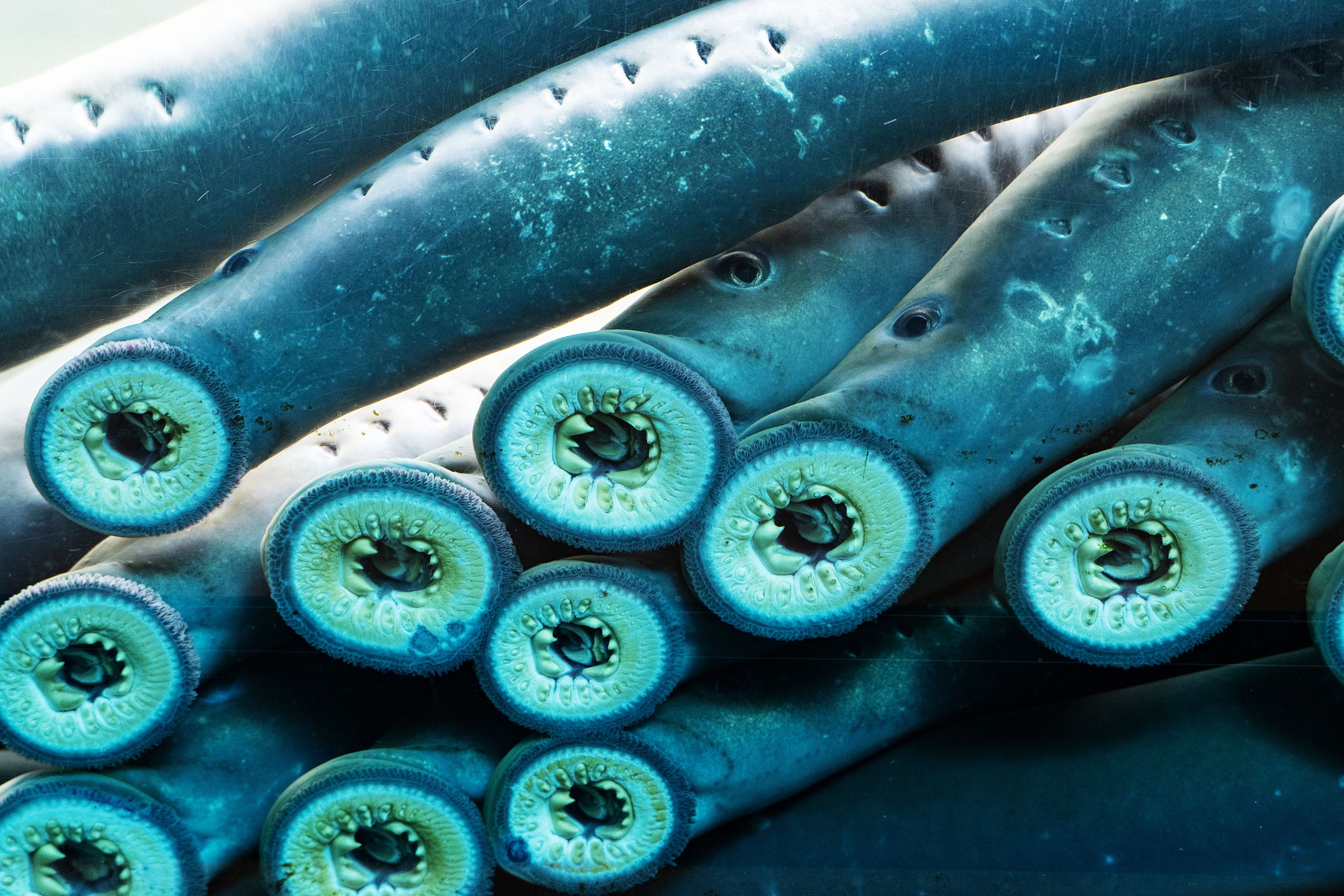

But outside the tribes, education remains a challenge. “The general perception is that lampreys are ugly, gross, and dangerous,” remarks Christina Wang of the US Fish and Wildlife Service’s Columbia River Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office. “Newspapers keep running headlines like ‘Blood-Sucking Vampire Fish. Save Them or Kill Them?’ People, especially transplants from the Midwest, get creeped out by lampreys. I’ve been a lamprey biologist for 20 years. When I started, the only people who cared about lampreys were the tribes. Now we’re getting through to more people. We have an exhibit at the Oregon Zoo. The general person comes up and says, ‘Oh, are you trying to get rid of them? Are they going to attach to our legs?’ But then we tell them the facts, and they change their minds.”

Unlike sea lampreys, Pacific lampreys can climb sheer waterfalls, sucking on and resting as they go. But they have trouble with the rough, sharp edges of traditional fish ladders. So the US Army Corps of Engineers, a partner in the multi-entity Pacific Lamprey Conservation Initiative, has designed near-vertical, aluminum lamprey ramps with resting pools that allow a large percentage of lampreys to make it over Columbia River dams.

In the river, Pacific lampreys face swarms of nonnative predators like smallmouth bass, striped bass, and walleyes, as well as an unnatural superabundance of native predators created by the impoundments and by the lampreys and other sea-run fish being massed against the dams. These predators include sturgeon, sea lions, seals, gulls, terns, cormorants, and northern pikeminnows. The Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission even pays a bounty on pikeminnows.

Predators, habitat destruction, global warming, and past persecution of lampreys—including by managers using the fish-poison rotenone—have reduced Pacific lampreys to the point that the only place the tribes can now legally catch them is Willamette Falls on the Willamette River.