Winging it

Once again, your intrepid robotics reporter finds himself in the warm embrace of the Bay. To paraphrase Mark Twain, the warmest I was ever embraced was early summer in Santa Clara. I’m writing this from a juice place in Palo Alto (living the dream), having finished a pair of back-to-back meetings nearby.

This week’s big Apple event brought me out here. As strange as it is to say, I’ve thus far missed the eye-burning smoke of Nova Scotia wildfires by traveling west to California. Very strange to view the apocalyptic New York skyline from afar. Though I suppose predictability is an element of climate change we’re going to be grappling with for . . . I don’t know, ever, probably.

I’ve covered the Apple experience a bunch this week. If you have time to read only one thing I wrote on the Vision Pro headset, I’d recommend this. It’s mostly about positioning and market fit. There’s not a ton about the system that’s applicable to the manner of stuff you normally encounter in this newsletter, but questions of scalability remain up in the air — mass production of sensors and components tend to find their way into robots eventually. There are also some interesting pieces of imaging onboard that could have some mapping applications.

Apple is still firmly in the lidar camp — gotta do something with all those years of self-driving car research, I suppose. As this form factor (theoretically) grows in popularity, I’m sure we’ll be having a lot of conversations around teleoperation as well. Simulations, too. After all, the product ended up being quite a bit more enterprise-focused than we initially suspected, based on Apple’s track record. More details between now and its early 2024 launch, no doubt.

I stuck around the Yay Area for a few extra days to take meetings. I’ve been trying to spend some time in and around Alphabet X for a while now (who hasn’t?). I got pretty close on my last visit, when I was out here for I/O, but ironically, the Intrinsic team was on the East Coast while I was out west for a big Google event. Turned out Apple week worked a lot better for all parties.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

After recording a quick episode of the TechCrunch Podcast (coming tomorrow) in a Santa Clara hotel that shares a parking lot with Levi’s Stadium and Great America, I hitched a ride up north to Palo Alto to get some demos from the Wing team. It was fortuitous timing, as the Alphabet X spinoff just released additional videos of its AutoLoader system.

The AutoLoader name misleads slightly. It’s actually a fully passive system with a minimal footprint designed to sit in a store’s parking lot. It’s about four feet tall, with a pair of (much taller) PVC poles that jut out like antlers. The image I took above is of a final version of the system. It’s more or less the same hardware as the kind you see in Wing’s demos, but recolored and badged with the company’s branding.

CEO Adam Woodworth tells me that the hardware was developed to work with stores’ existing workflows. Wing benefited from the pandemic in a roundabout way. When stores shifted to curbside pickup, suddenly a lot of parking lot space was freed up. It’s a change that frees up the employee from having to wait around for the drone to arrive and manually attach the payload to its tether.

“The original idea for this was: Could you just bolt it to the [curbside pickup] sign?” says Woodworth. “The opportunity exists with the existing workflow. How can you make it so the airplane works like a car that’s driving up? How do you make it so the plane picks up the box, rather than the person having to time sync it there? It took a long time to get a robust mechanical solution for that that didn’t require more electronics.”

Image Credits: Brian Heater

The AutoLoader is designed to effectively sit where customer cars pull up, meaning the employee doesn’t have to change much behavior to adjust. Rather than handing a product through the car window, however, they take the special Wing box (which looks a bit like a Happy Meal, with plastic rings up top), lining the holes with a pair of pegs on the AutoLoader. The company says training employees takes roughly 20 seconds — the main thing is knowing which side (white) of the box faces out.

When it arrives, the drone hovers above to scope out the AutoLoader. If it encounters an issue it can’t correct for (e.g., the employee forgot to bring the box out), it will return back to base — one of the downsides of the passive system is that the AutoLoader can’t communicate an issue before the drone arrives. If things look good, it lowers the tether. The large poles keep the attachment in place, before it begins to retract, latches on to the top of the box, and takes the payload with it.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

Once the drone reaches the delivery point, it slowly lowers the box down to a predetermined delivery spot on the ground. The area needs to be at least roughly six feet by six feet, with no tree coverage to block its view. Granted, it was a relatively short distance from one end of the Wing offices to the other, but things went as planned in our two demos. The second time, I asked a Wing employee to put a soda in the box. When the payload landed, he removed the Coke bottle, opened the cap and took a drink without a carbonation explosion.

The tests in the area are limited to the Google satellite campus, but the area’s suburban sprawl make it a good potential market for Wing. Drone delivery has always seemed to make the most sense in remote areas or places without modern infrastructure. A drone can get things from point A to point B more quickly when it doesn’t have to bother with crumbling roads and impenetrable traffic (granted, the latter certainly applies to large swaths of the Bay).

“My belief on this is that delivery is always going to require a bunch of different offerings, in the same way that, if you show up to an airport, there’s short-haul flights and long-haul flights and there’s aircraft designed to take 300 people across an ocean,” says Woodworth. “The market segment that we focus the most on is dense suburban, getting close to rural. There’s immense amount of demand there. That’s where people get the sort of order numbers that skyrocketed over the pandemic.”

Wing drones have made more than 340,000 deliveries to date, across Australia, the U.S. and a handful of smaller spots in Europe. The company says it’s built “thousands” of drones so far. Current customers have up to 50 drones in a location, but the “sweet spot” is around 20 to 30.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

From the Palo Alto offices, it was a 12-minute drive to Wing birthplace Alphabet X in neighboring Mountain View. Like the area that surrounds it, the site has been through tremendous transformation over the past 70 years. At the tail end of the ’50s, the San Francisco Bay Area Curling Club (which is still alive today) opened a rink on the lot. In the middle of the following decade, the site became home to Northern California’s first enclosed air-conditioned shopping center, the Mayfield Mall, which boasted 60 stores, anchored by JCPenney.

In the mid-’80s, HP (which maintains its global HQ between Wing and Tesla) converted the building into a service center that operated through 2003. The massive building sat dormant for the next dozen years, until Google X set up shop. An employee gave me the public tour of the space — so-called because the secrecy vibe is strong within these walls. The air of mystery is still very much the appeal, and it appears that many or most employees have gone back to the office. It’s as big and cavernous as one would expect from a former mall.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

Things have been retrofitted, of course. Escalators were turned into stairways, the carpeted mall aesthetic has given way to a reclaimed wood and Edison-style LED bulb coffee shop vibe, outfitted with all mod startup cons. We went for lunch in the cafeteria, and I made a salad next to the metal conveyor belt sushi bar. On a table in the waiting area of the lobby sits a custom chess set, on which rests 3D-printed pieces, each representing Alphabet X companies and philosophies, like the Monkey Pedestal Problem. From a blog post published the year after the company moved into the space:

Let’s say you’re trying to teach a monkey how to recite Shakespeare while on a pedestal. How should you allocate your time and money between training the monkey and building the pedestal? The right answer, of course, is to spend zero time thinking about the pedestal. But I bet at least a couple of people will rush off and start building a really great pedestal first. Why? Because at some point the boss is going to pop by and ask for a status update — and you want to be able to show off something other than a long list of reasons why teaching a monkey to talk is really, really hard.

Tell me about it.

Image Credits: Loon/Alphabet X

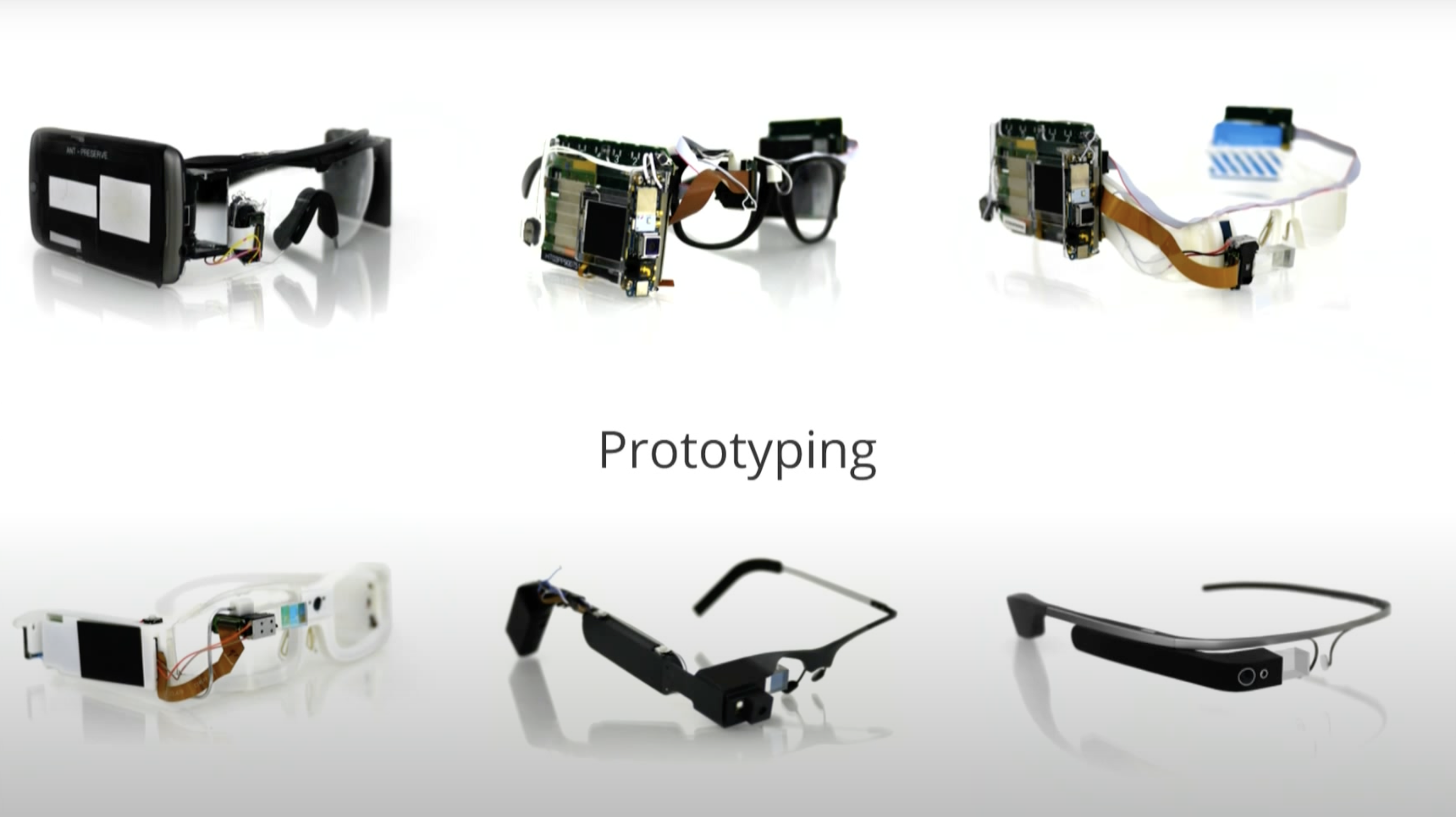

There’s also a small museum devoted to different X projects that includes a Loon Balloon and the “sharkie slippers” worn to work on the material without damaging it (turns out the team was made up of a bunch of San Jose Sharks hockey fans). Another exhibit features the earliest iterations of Google Glass, which were — as you might expect — a bunch of electronics glued to existing glass, including an iconic set with rhinestones. On one wall, an exhibit devoted to ocean sustainability company Tidal features a trio of plastic fish used in early demos. Press a button beneath the one in the middle and it starts belting out a song, Billy Bass style.

Image Credits: Google (opens in a new window)

Various early Wing prototypes hang from the ceiling, bringing us close to something resembling its present-day craft. At the other end, the door is flanked by a Waymo car resembling a Mini Cooper or “New” VW Bug and Mineral’s agtech robotic, which was much taller in person than I’d anticipated. The system sits atop two large panels, leaving several feet of space in the middle, so it can cruise between crops to growth without damaging them in the process.

Image Credits: Mineral

Mineral is an interesting example of the work that goes on here. Much like the bygone Everyday Robot project, the company ended up designing hardware because the systems it needed to execute its software and data collection work just didn’t exist in the world. Something that often gets lost in the conversation around this stuff is that Google has the resources to allow a team to just go ahead and, say, build robots for other work — robots that end up looking pretty good, courtesy of some great in-house industrial design. These things generally aren’t designed for mass production, however.

The end results of these projects are a mixed bag. Some, like Glass, Android Wear and Brain, end up getting absorbed into the parent company. Others, like Waymo, Wing, Loon and Intrinsic, graduate into their own Alphabet-support companies to varying success. Others still never make it out of the labs — you mostly don’t hear about those, beyond the occasional rumor.

Image Credits: Alphabet X

X was, of course, impacted by the recent major round of layoffs. Everyday Robots scattered to the wind, with much of the team being absorbed into DeepMind, which continues to operate its own discrete DeepMind robotics team. In late 2021, Actuator broke the news of Smarty Pants, a soft robotic exoskeleton project. Following the recent shakeups, that research has spun out into Skip, which operates independently of Alphabet — that’s the final potential route for these projects. Ear-worn biomarker detection project NextSense, for example, also spun out into its own startup.

The company itself remains relatively independent from the rest of Alphabet. There’s collaboration, of course, but X’s lab projects are focused mostly on the world’s problems, not Google’s. As such, roughly 50% of its portfolio is currently focused on climate change. The exact number of companies that live under the X umbrella remains a mystery (one of many). Alphabet says it’s ever changing and sometimes difficult to quantify, with some early-stage projects employing only one or two staffers.

Dave Zito (Miso Robotics) and Julia Collins (Zume Pizza) at TechCrunch Disrupt SF 2017 Image Credits: TechCrunch

A requiem today for another company that didn’t make it. After banking $500 million in funding, Zume Inc. announced that it was closing its doors late last week. TechCrunch readers are likely familiar with Zume as a pizza robotics firm. Co-founders Julia Collins and Alex Garden announced a $48 million round onstage at Disrupt 2017.

Here’s what I wrote at the time:

Zume’s ambitions are broader than that. Collins joked at Disrupt about not expecting to be known as the “pizza robot company.” That kind of moniker will likely be tough to shake in these early stages, because, well, pizza robots are basically all the things the internet enjoys in one. Pizza was a logical first step for a company looking to prove its automation delivery method, but Collins and Garden have often discussed plans to build an “Amazon of Food.” Of course, Amazon is also the Amazon of food (and the Amazon of everything else, really), but the broader point remains.

Image Credits: Zume

This is an important point. The world saw Zume as a pizza robotics company, because Zume made pizza robots. Makes sense. They parked one of their food trucks outside the Disrupt venue that year and served pizza to attendees. It was very much their public-facing offering. In various conversations, the founders told me that their “secret sauce” was not tomato — rather it was fleet management software/AI designed to optimize delivery routes and coverage. That planned pivot is fairly common in this world.

In 2019, however, came an unplanned pivot to plant-based plastic packing. From the outside, it’s hard to say whether Zume expected a full turnaround or was simply trying to maximize returns for very generous backers after its initial plans fell through. Bloomberg says sliding cheese was partially to blame, writing, “challenges, such as keeping melting cheese from sliding off while the pizzas baked in moving trucks.”

If reading mass market business books have taught me anything, it’s the need for maintaining stationary cheese.

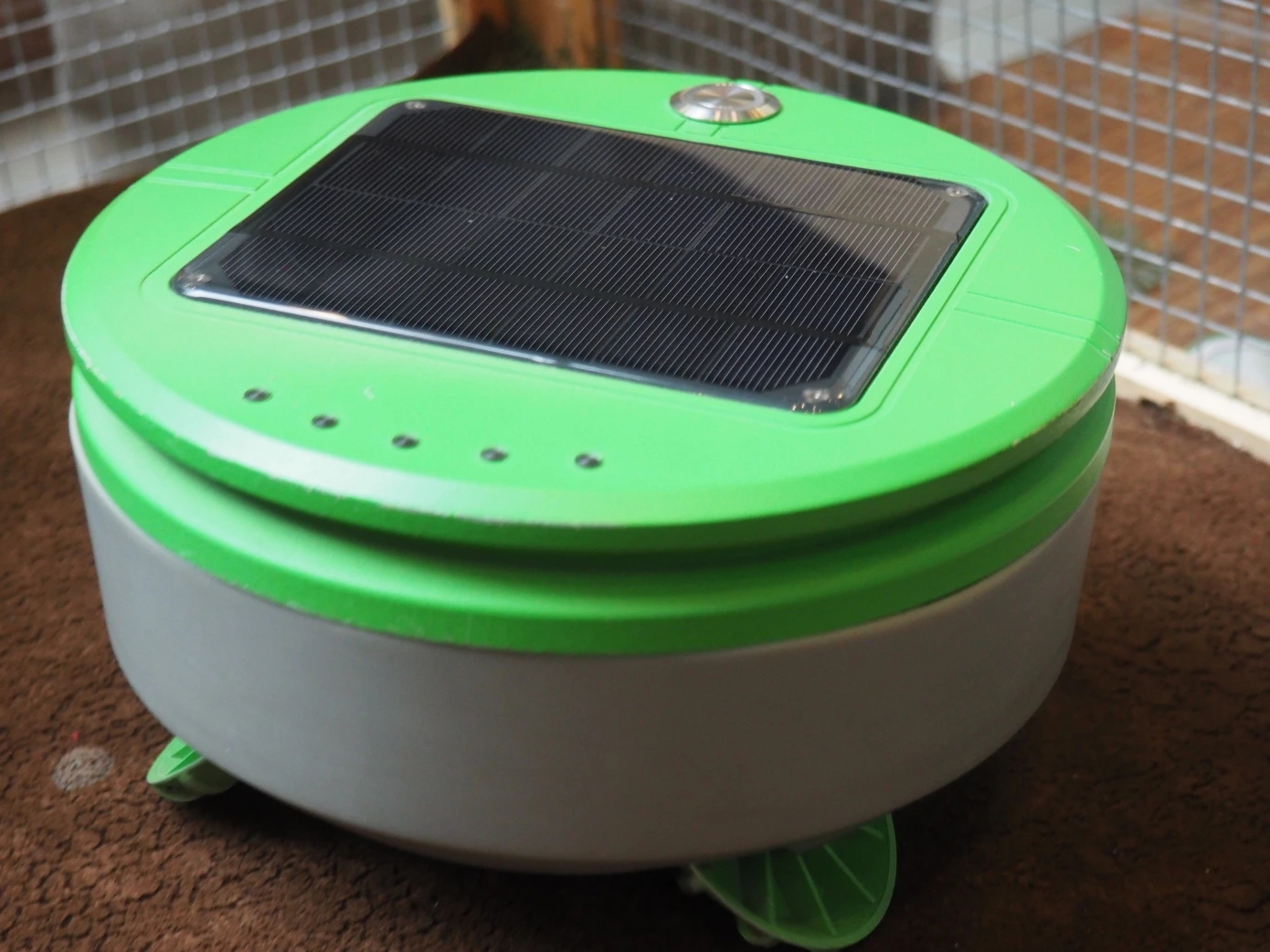

Image Credits: Brian Heater

I was at TechCrunch for exactly three months when Franklin Robotics participated in our first robotics pitch-off. The company was showing a very early 3D-printed version of its Tertill robot. The “Roomba for weeds” framing wrote itself. It didn’t hurt that the company employed a number of iRobot ex-pats, including CTO Joe Jones, who had been the robotic vacuum company’s first full-time hire.

Joe Jones had founded Harvest Automation nine years prior, along with fellow ex-iRoboters Clara Vu (Veo Robotics) and Paul Sandin (formerly of RightHand Robotics). The team continues to be led by CEO Charles Grinnell. Harvest offers a wide range of use cases, primarily focusing on industrial robotics for agtech environments like greenhouses.

On Wednesday, the two firms announced a merger, forming a combined company also named Harvest Automation. Franklin/Tertill co-founder Rory MacKean will become COO, with Grinnell maintaining the CEO gig. The co-founder of iRobot, Helen Greiner, who stepped into the Tertill CEO role in late 2020, will remain on the Harvest board. There’s a clear agtech through line uniting the two companies, though their products, the Tertill and HV-100, target extremely different markets.

“Harnessing the experience of both companies, we will deliver farm tough, low cost robots to the specialty crop sector,” Greiner told TechCrunch.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

Boston Dynamics’ Spot gets a little smarter this week, with a 3.3 software update that brings additional visual, thermal and acoustic inspection capabilities. Also of note: The company announced that more than 1,000 of the quadrupedal robots have been deployed in 35 countries. That’s not including my new LEGO set, mind.

I also unfortunately let this one slip through the cracks the other week (between I/O, Automate and WWDC, my inbox is a dystopian hellscape — so apologies to anyone who has attempted to contact me over the last month), but Agility CEO Damion Shelton wrote to tell me about some of the things the company has been toying with around generative AI, including controlling Digit with GPT.

Says Shelton:

Not faked — code-gen occurs in real time based on the actual voice prompt. In the past, you’ve asked, “Why humanoids?” One answer based on this test would be “humanoids share a way of interacting with the world that is semantically similar to how people work, allowing us to leverage generative AIs that were not designed for robot control.”

Image Credits: Agility

And quoting from the video:

In this demonstration, Digit starts out knowing there is trash on the floor and bins are used for recycling/trash. We use a voice command “clean up this mess” to have Digit help us. Digit hears the command and uses an LLM to interpret how best to achieve the stated goal with its existing physical capabilities. At no point is Digit instructed on how to clean or what a mess is. This is an example of bridging the conversational nature of Chat GPT and other LLMs to generate real-world physical action.

The video is worth watching, if only to get a clear visual representation of the debate around the efficacy of using generative AI to control robots. I’ve been mulling over a larger piece on the subject after some enlightening conversations at this year’s ProMat and Automate. Maybe I’ll finally tackle that when travel slows down a bit. Curious to get folks’ take on the subject and start detangling the hype from potentially truly useful low- and no-code robotic interactions.

Image Credits: Bryce Durbin / TechCrunch

A new robotics newsletter will be waiting in the wings each week when you subscribe to Actuator.