The All-American Myth of the TikTok Spy

The form reached my inbox as part of routine paperwork, but I sensed a tinge of accusation. I had been invited to speak at a national laboratory. In order to access the facility, I was required to attest that I wasn’t a participant in a foreign talent recruitment program. China, my birth country, topped a short list of “countries of risk.”

I found the vigilance slightly amusing. I was going to give a talk! In a dash of mischievousness, I thought of scrawling over the form: “D-I-S-S-I-D-E-N-T!”

I have never liked the word “dissident” or claimed to be one, though others have labeled me as such. The point of the story is not that I’m special, but that I should have nothing to prove in the first place. No amount of public critique of Beijing’s policies or the personal cost dissent exacts can spare me from the extra scrutiny. As a Chinese person living in the US, I’m often treated as a potential spy before I’m seen as a human being.

Espionage was once considered antithetical to American individualism. The term invoked imperial European courts—the word spy originated from Old French, espie—and British secret agents, symbols of an old world that the young republic was trying to break away and distinguish itself from. The carnage of World War II shattered America’s isolationist proposition. Joining its newly founded clandestine services was lauded as patriotic. In the long shadows of the Cold War, the enemy agent in the popular imagination was someone hiding a Russian accent. Three decades after the fall of the Soviet Union, as China emerges as a new superpower and contests US hegemony, the face of foreign espionage in the West has become Chinese.

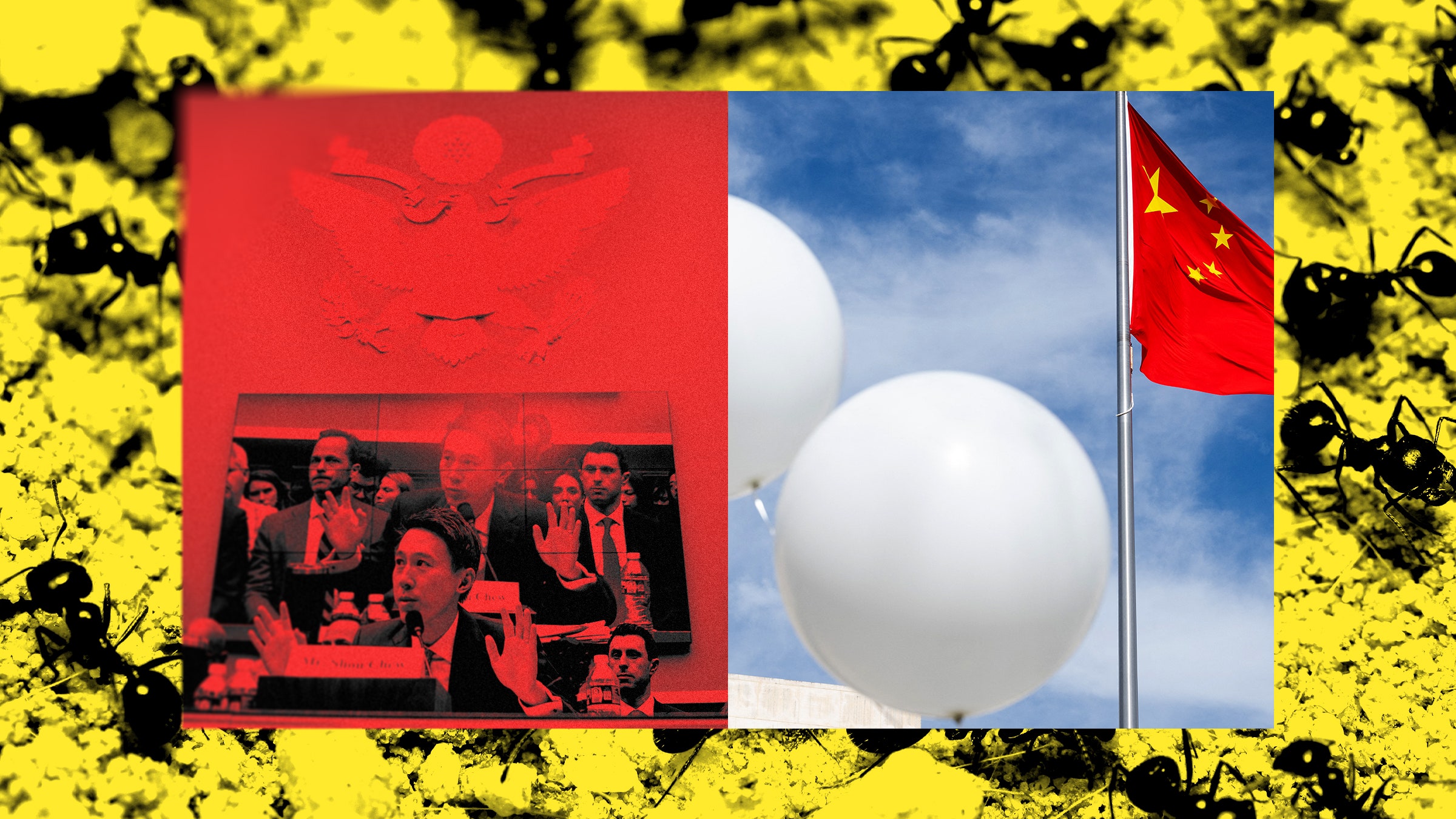

It’s not just that Chinese students and scientists are routinely depicted as puppets of Beijing and conduits of intellectual property theft. The tint of racialized suspicion has seeped into anything “made in China.” Communications equipment from Huawei and ZTE are lurking in the airwaves. TikTok is “the spy in Americans’ pockets.” US authorities deem Chinese-manufactured cargo cranes a possible national security threat; in the words of a former head of counterintelligence, “cranes can be the new Huawei.” The acquisition of American farmlands by Chinese firms has also been met with alarm: The properties could be used as a “perch for spying,” so the argument goes. When a Chinese high-altitude surveillance balloon flew across parts of the US before it was shot down over the Atlantic, the mass hysteria had less to do with the balloon itself—even the Pentagon acknowledged it posed minimal risk—and more to do with the state of the national psyche. The floating object was the materialization of a constant dread, the embodiment of an alien intrusion.

Each time an objectionable act becomes racialized, such as how “crime” is coded as Black and “terrorism” as Muslim after 9/11, the problem is not that every individual from the minority group is innocent but that the collective is regarded as uniquely guilty, and anyone who shares the identity is implicated by association. The ethnicization of espionage in the US as a distinctly Chinese threat is rooted in centuries-old Orientalism and reinforces racial stereotypes. The rhetoric is weaponized to expand state power and advance special interests. The illusion of protection by discriminatory means obscures fundamental questions about our relationships with technology and the state, as well as how to navigate between our intimate and communal selves. In a world of privatized commons and militarized borders, who sees or cannot be seen? For whose benefit, and to what end?

A prominent 19th-century science manual instructs that a person’s “faculty of Secretiveness” can be measured by how much the shape of the nostrils resembles that of a Chinese nose. Published in New York in 1849, the book asserts that the people of China “are the most remarkable people in the world for secretiveness.” This view, widely held at the time, was echoed by the American diplomat and travel writer Bayard Taylor, who claimed that “the Chinese are, morally, the most debased people on the face of the earth,” whose “character cannot even be hinted.”

As waves of Chinese migrants left a crumbling Qing empire for distant shores, their presence disrupted a fragile white identity based on native dispossession and the transatlantic slave trade. Moral panic ensued. Popular literature described the Chinese people as mysterious, with inner worlds as cryptic as their written script. The new arrivals were treated as an invading species, who were stealing jobs, spreading disease, and corrupting the body politic.

In 1912, the British novelist Sax Rohmer, a white man, invented a character who epitomized the West’s fears and fantasies about the Orient: Dr. Fu Manchu. The supervillain and mad scientist is “Yellow Peril incarnate.” Inspired by the works of Bayard Taylor, Rohmer described Fu Manchu’s face as inscrutable, an impenetrable mask concealing his evil plots. Ironically, in over a dozen film adaptations over the decades, the character has only been played by white actors.

The projection of one’s insecurities onto the other is always riddled with contradictions. In the West, the Chinese people are portrayed as both primitive—so they need to steal technology—and scientifically advanced, with superior spying capabilities. The Middle Kingdom is either hopelessly stuck in the past or already inhabiting the future, where an ancient wisdom bestows startling foresight. The only consistency in these conflicting prejudices is an othering stance. The people of China are regarded as so radically different they’re relegated to a different temporal plane, while the present belongs to the West.

During the Mao era, Western writers used the phrase “blue ants” to describe the Chinese population, in reference to the light navy uniforms of the time. This image of the Chinese people as faceless, mindless automatons has also shaped American perceptions of Chinese spycraft, most notably in the so-called “thousand grains of sand” theory. Proposed by FBI analysts in the 1980s, the metaphor goes like this: To gather intelligence about a beach, the Russians would send in a submarine and frogmen, the Americans would use satellites, and the Chinese would simply dispatch a thousand tourists, each collecting a single grain of sand. The theory has been refuted—Beijing’s intelligence operations are not so different from those in other countries and mostly rely on professionals—but not before it had been hailed as doctrine for decades and cast a distorting light on every Chinese visitor as a potential foreign agent.

This February, during the first hearing by the newly established House Select Committee on China, former national security adviser H. R. McMaster described the pervasiveness of Chinese industrial espionage in graphic terms: “If you bolt your front door, they’re coming through the window. If you bolt your windows and put up screens, they’re going to tunnel under your house.” According to the retired general, the “many vectors of attack” demanded “a holistic approach.” As I listened to the hearing, I wondered how many who had heard these words pictured an army of ants creeping through the cracks, sweeping up every grain of sand.

Three days before its debut hearing, the House Select Committee on China held a rally and press conference in Manhattan, outside a commercial building in Chinatown.

"This innocent-looking building that you see behind me has an unauthorized secret police station linked to the Chinese Communist Party," said Congressman Mike Gallagher, who chairs the committee. According to law enforcement officials and some human rights groups, the Chinese government operates dozens of overseas police outposts, including three in the US, which can be used to surveil local Chinese communities and suppress dissent. Weeks after the press conference, the FBI arrested two men associated with the office in Manhattan on charges of conspiring to act as foreign agents and destroying evidence. On the same day, the Justice Department also charged 44 individuals, believed to be based in China, on crimes related to online harassment and intimidation against Chinese nationals in the US.

I watched a video of the press conference. Members of the Chinese and Tibetan diaspora stood behind the congressional delegates. They held up signs that read “Condemn the CCP’s transnational repression.” But one item from the demonstration caught my attention: a pale balloon with a Chinese national flag sticker on one side, and three letters on the other, “SPY.”

I reckon that the choice of prop might have been tactical. By holding up a white party balloon, the protesters were trying to invoke a common angst over Beijing’s aggression. For those of us who have crossed oceans and political systems, to still live under the watchful eyes of the home government can be a profoundly lonely experience, not unlike that of being a racialized minority. In the words of a Chinese human rights activist who spoke at the rally, “This is the first time that the Chinese basic community feel that their grievance is heard by the American public.”

However, the emotional appeal from minority members for official intervention can inadvertently imperil the same communities in need of protection. By casting violations of civil liberties through the sweeping lens of national security, Washington’s hardened response helps fuel racial bias, which can easily mistake targets of transnational repression as its suspected perpetrators. The emphasis on legal status and political allegiance in immigrant communities normalizes the nation and its borders, and reinforces a Cold War binarism where China and the US stand as polar opposites.

In 2001, as a member of the Washington state legislature, Representative Cathy McMorris Rodgers blocked a bill that would replace the word “Oriental” with “Asian” in official documents. This March, at the highly anticipated congressional hearing featuring TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew, Rodgers, now chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, declared at the start, “We do not trust that TikTok will ever embrace American values.”

For the next five and a half hours, Chew, who is Singaporean of Chinese descent, tried valiantly to distance his employer as well as himself from ties to China. During his five-minute opening remarks, Chew mentioned his Singaporean upbringing, his education in the UK and the US, and that his wife was born in Virginia. In response to questions of whether TikTok or its parent company ByteDance is “a Chinese company,” Chew was evasive: “What is a company that is now global?”

Chew’s responses, packaged in notably Americanized English, did little to assuage skeptics on the committee. Many lawmakers believe the short-video app is a weapon in disguise, developed by a foreign adversary to poison American minds and extract Americans’ data. One piece of evidence, repeatedly cited to corroborate the claim that TikTok is de facto spyware, is China’s National Intelligence Law. Enacted in 2017, the legislation states that “all organizations and citizens shall support, assist, and cooperate with national intelligence efforts.”

The focus on the Chinese government’s subpoena power as a unique feature of its authoritarian system overlooks the many ways American companies cooperate with the state. Local and federal law enforcement routinely utilize access to social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook, private security cameras, and cell phone networks to criminalize and surveil, at times without proper authorization. The sweeps have been directed against migrants at the southern border, people seeking abortion services, and Black Lives Matter protesters. On the other hand, Chinese companies like Alibaba and Tencent have refused requests from state agencies to hand over customer data.

The caricature of an almighty Beijing with absolute control feeds into the age-old misconception that the Chinese people are submissive subjects devoid of individual agency, who can only act out of national loyalty or political coercion, but never for personal interest or financial gain like their counterparts in the West. While the ruling party of China is nominally communist and maintains a Leninist structure, the country has been an integral player in global capitalism for decades. Yet, during the TikTok hearing, the word “communist” is frequently uttered, not to inform but to exoticize. The tone is reminiscent of an earlier era, when the United States claimed the holy mantle to save the colored masses of the world from the red menace.

TikTok is not a product of communism but of surveillance capitalism. As China moves from the margins to the center of global capitalism, the panic over Chinese espionage is inseparable from the apprehension about the West in decline. History repeats itself as Florida and several other states pass or propose legislation restricting Chinese citizens from purchasing property, citing security concerns. Similar excuses were used for the “alien land laws” in the early 1900s that barred Chinese and Japanese immigrants from land ownership. The spying allegations against TikTok and other Chinese products are often hypothetical: It’s not so much about what the companies have done or even what they can do; China is used as a foil to project American fears and desires. After all, the US military and intelligence agencies are pioneers in surveillance technology and foreign interference. As it was in the aftermath of 9/11, a perceived threat is used to justify massive expansions of executive power, which also include the ability to monitor and manipulate, both at home and abroad. The Senate bill to ban TikTok has been aptly called a “Patriot Act for the internet.”

To continue operating in the US under ByteDance ownership, TikTok has proposed to store American user data exclusively on US-based servers run by Oracle. The plan, Project Texas, is named after the state Oracle is headquartered in. The software giant, proudly American, boasts clients that include “all four branches of the US military,” the CIA, and local law enforcement. It has also marketed surveillance tools to Chinese police. Without universal data protection standards, the mere imposition of a national border around data does little to mitigate risk or reduce harm; instead, the border only helps determine who has the right to exploit the data and commit harm.

Oracle is one of the largest data brokers in the world. In a report released in June, the US Intelligence Community acknowledged that commercially available information, which “includes information on nearly everyone,” has reached a scale and sophistication on par with targeted, more intrusive surveillance techniques. The private data market is loosely regulated and open to all. US spy agencies are among its countless clients.

“Everyone is being surveilled constantly, but it’s always ‘Shoot the balloon!’ and never ‘Unplug Alexa.’” This line, delivered by comedian Bowen Yang on Saturday Night Live, encapsulates the quotidian reality of mass surveillance and the hypocrisy in official responses. After capitalism has commodified just about everything that sustains life—land, water, health care, to name a few, its latest site of extraction is life itself: our time, attention, movements, and presence. All can be captured, converted into data, and traded as commerce.

For years, this virtually unfettered transaction has benefited US companies and is aligned with Washington’s agenda. China’s economic rise, coupled with Beijing’s belligerence, has shifted this calculus. As US authorities place more restrictions on the transnational exchange of money, goods, information, and people in the name of security, at times in conflict with the demands of capital, the two superpowers increasingly mirror each other in their paranoia and protectionist stance. The Chinese government recently revised its anti-espionage legislation. The new law, which went into effect on July 1, broadens the definition of spying, grants the state more power to inspect facilities and electronic devices, and further limits foreign access to domestic data. Citing the new legislation, China’s Ministry of State Security proclaimed in a social media post that “Counterespionage needs mobilization from all of society,” while FBI director Christopher Wray has repeatedly stated that a “whole-of-society” approach is necessary to fight against threats from China. In Beijing's propaganda materials alerting Chinese citizens of foreign intelligence activities, the spy is routinely depicted as a white man.

The bodies we inhabit are never ours alone. In the age of surveillance capitalism, the bounds of our private existence are endlessly encroached on by the richest and mightiest of interests, who also dictate the terms of extraction and exploitation. In this uneven battle, privacy is more than an individual right; it’s a form of communal care. An encrypted message requires effort and trust from both the sender and the receiver. The decisions we make about seeing or not being seen also configure the spaces we move in; they affect how others see and are seen. To reclaim our sovereign yet porous selves, we must reimagine space—physical as well as digital, social as well as legal—and interrogate its many borders: around nation, race, gender, class, property and the commons.

What if safety is achieved not by violent organs of the state but through their abolition? What if we reject the false binaries proposed by status quo powers and choose liberation? What if, instead of imprisoning our identities within predefined labels, we refuse to be categorized? What if we make ourselves illegible to convention, corrupt the code, glitch the mainframe, and disrupt the ceaseless flow of datafication? A secret language opens up pathways to fugitive spaces, where an uncompromised presence is restored and alternative futures are in rehearsal.