Earth’s ozone layer is on the mend

For decades, the Earth’s ozone layer, which protects life on our planet from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet (UV) rays, has taken a beating from common chemicals used in everything from refrigerants to hairspray. But now the holes in the ozone layer are diminishing, thanks to a decades-long global effort to repair it, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) confirmed yesterday.

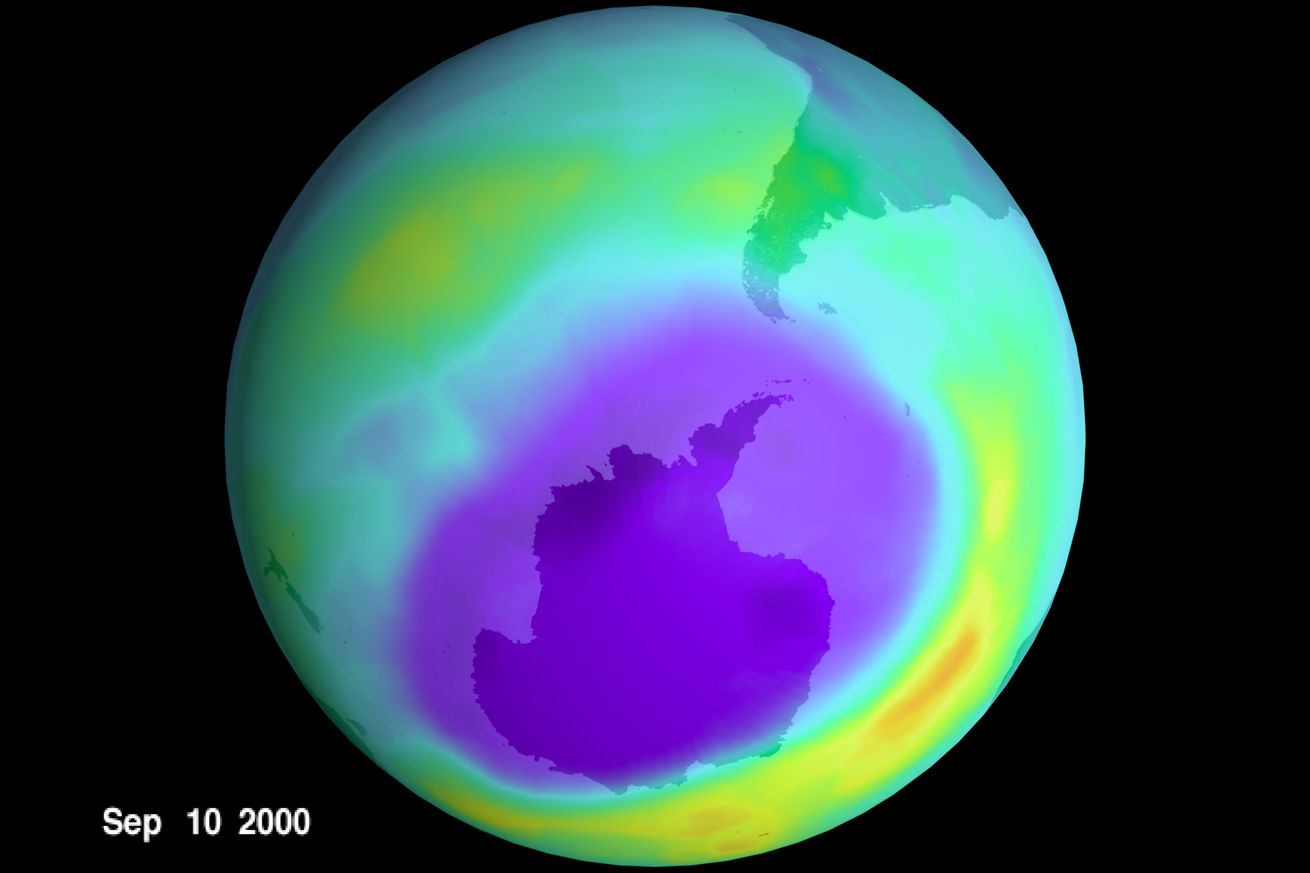

Scientists first discovered a gaping hole over the Antarctic in 1985. A couple years later, countries around the world adopted the Montreal Protocol, a global effort to phase out “ozone-depleting substances.” And now, thanks to that work, scientists expect the ozone layer to start looking more like its normal, healthy self in the coming decades. That lowers the risk of skin cancer and cataracts in people, as well as sun damage to plants and crops.

Scientists expect the ozone layer to start looking more like its normal, healthy self in the coming decades

By around 2066, the WMO thinks the ozone layer will be back to what it was in 1980 over the Antarctic — before there was that gaping hole. Since ozone thinning has been the most severe there, other areas are expected to recover sooner. Up north over the Arctic, the ozone layer should look as it did in 1980 by 2045. For the rest of the world, that recovery is expected by 2040. A United Nations panel of experts presented those findings yesterday during the American Meteorological Society’s annual meeting. Of course, that progress is contingent on keeping policies in place that limit those pesky ozone-depleting substances.

Ozone molecules in the stratosphere absorb damaging UV-B radiation from the sun, keeping much of it from reaching us. That’s part of a process of constant ozone creation and destruction in our atmosphere. But when certain chemicals waft up there, that balance is thrown off — causing more ozone to be destroyed than created.

Some of the worst offenders are chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) once used in refrigeration, air conditioning, aerosol sprays, and a host of other products. Then there are hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), developed as less potent replacements for CFCs that nevertheless still chewed through the ozone layer. Fortunately, by now, the Montreal Protocol has succeeded in phasing out about 99 percent of ozone-depleting substances.

The global agreement to protect the ozone layer is also beneficial for efforts to slow climate change. Ozone-depleting substances were replaced with another class of chemicals that happen to be potent greenhouse gases, called hydrofluorocarbons (or HFCs — pardon all the annoyingly similar acronyms). The Kigali Agreement was added to the Montreal Agreement in 2016 to limit those planet-heating chemicals. Axing HFCs globally is expected to reduce global warming significantly — up to half a degree Celsius by 2100. For context, the world has already warmed by about 1.2 degrees Celsius since the preindustrial era — exacerbating many of the extreme weather disasters we live with today.

But there is a climate caveat with the WMO’s good news. The panel of experts warns that “geoengineering” — intentionally manipulating the climate and / or atmosphere to undo some of the damage we’ve done by burning fossil fuels — could potentially take its own toll on the ozone layer. They’re particularly concerned about a tactic called stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI).

Proponents think that tactic could help cool the planet because the aerosols might reflect some sunlight back into space. But SAI “comes with significant risks and can cause unintended consequences,” according to a recent WMO-backed report. And some climate experts have already sounded alarm bells over one startup’s recent attempted release of reflective sulfur particles in the stratosphere.

Nevertheless, the phaseout of ozone-depleting chemicals is held up as an example of what people can accomplish when they tackle a global environmental crisis together. “Ozone action sets a precedent for climate action. Our success in phasing out ozone-eating chemicals shows us what can and must be done — as a matter of urgency — to transition away from fossil fuels, reduce greenhouse gases and so limit temperature increase,” WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas said in a statement yesterday.