Hope on the Front Lines of the Drug Overdose Crisis

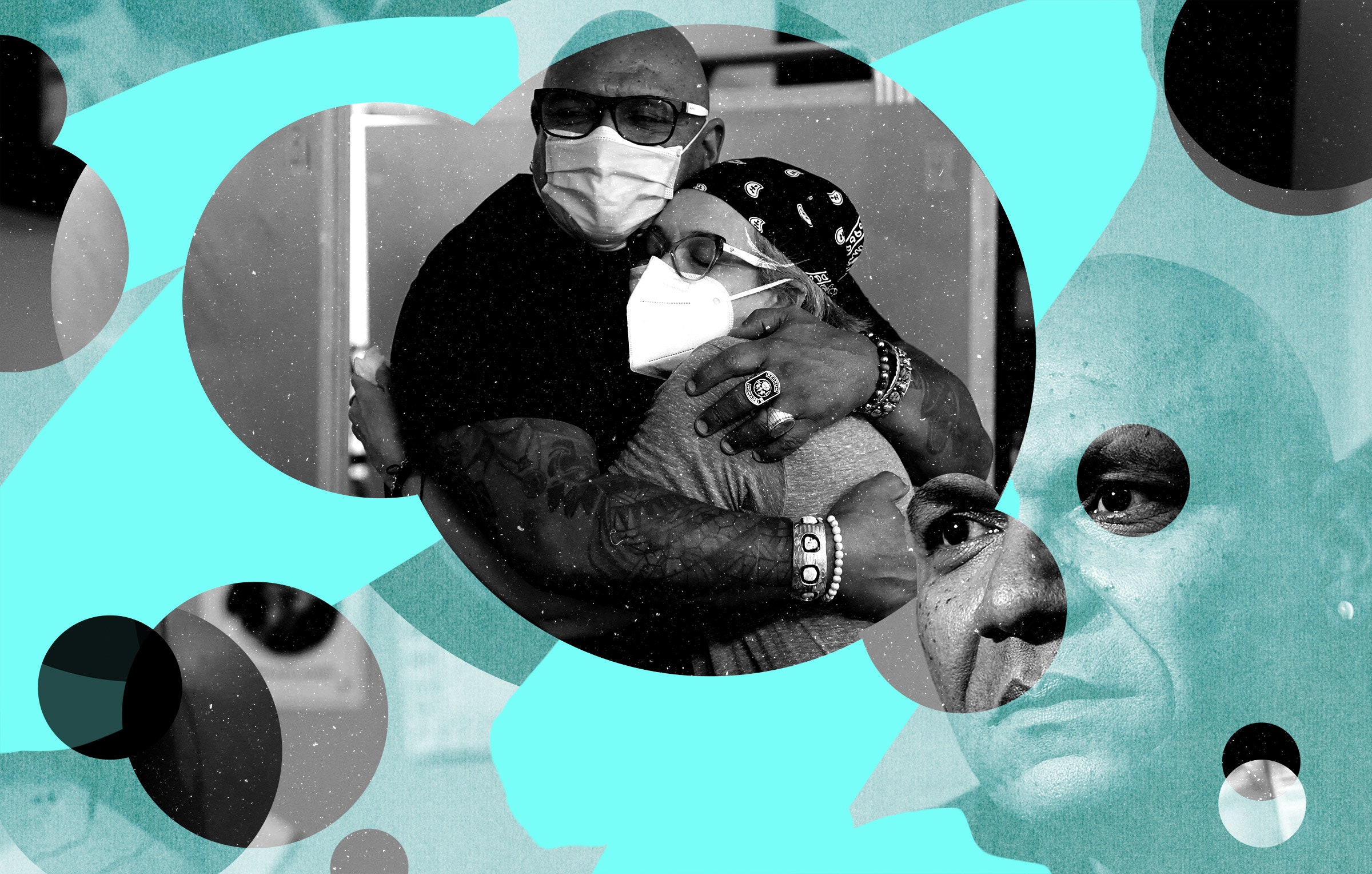

It’s hard to find good news about the overdose crisis. The drug supply is poisoned. Year after year, the death rate rises. It’s grim. Yet people like Sam Rivera still believe things can change for the better. Actually, nevermind believe—he’s actively working toward those changes, one hot meal, warm shower, and heartfelt conversation at a time.

Rivera runs OnPoint, a New York–based nonprofit focused on helping drug users stay safe. Many of the services it offers resemble what you’d find from more traditional addiction-treatment programs: mental health counseling, acupuncture, free coffee and meals. But OnPoint gained national attention in November 2021 when it opened the first two sanctioned overdose prevention centers (OPCs) in the United States. These spaces permit people to use drugs under supervision; staff monitor the participants to make sure they’re OK, providing oxygen, naloxone, and other support if they show signs of overdose.

In Europe and Canada, OPCs are well-established public health tools, and years of research indicate that they work. In the United States, they’ve been the subject of rancorous debate and angry opposition; critics argue that these programs make the drug crisis worse, despite evidence that they save lives. A long-gestating attempt to open a site in Philadelphia has been held up by a lawsuit. (The federal government sued the nonprofit Safehouse, arguing that a provision of the Controlled Substances Act colloquially known as the “crack house statute” renders overdose prevention spaces illegal.) Even in liberal California, Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed a bill to allow a pilot program just last year.

OnPoint opened its two Upper Manhattan locations, in East Harlem and Washington Heights, with support from local government. City officials pledged not to take legal action against it. Earlier this month, Mayor Eric Adams debuted a mental health agenda calling for more of these centers. As anyone paying even the most glancing attention to Adams’ career knows, he is not a progressive ideologue—he supports these programs because they work.

Rivera, for his part, is excited about OnPoint’s future. He’s had a long career in harm reduction, one that started more than 30 years ago, during the AIDS crisis. He rebukes the idea of “tough love,” so prevalent in mainstream addiction treatment. Instead, he has a far softer touch. On the phone, Rivera took every opportunity to emphasize the humanity of the people he helps. Treating people well, he believes, gives them the best chance to get well.

WIRED: Have attitudes toward harm reduction changed since the start of your career?

Sam Rivera: Yes. Although in some ways, I feel like it’s 1986. I remember when I was starting out and talking about syringe exchanges, it was very difficult. People thought we were crazy. We still have people today who believe we’re enabling drug use, but back then, they’d say stuff like, “Don’t give them syringes.”

In the past year and a half of operating the OPCs, treatment providers are working differently with us, and police are working differently with us. To have the NYPD [New York Police Department] be a partner in our work—if you told me that 30 years ago, I would’ve thought you were out of your mind. So that’s a major shift.

I read that OnPoint requires around $4.5 million per year to operate around-the-clock. How difficult or easy has it been to get the funding you need?

Very difficult. We’ve been staying afloat by fundraising, having the support of a number of amazing individuals and a few foundations. The part of our work that is looked at as the illegal element is the observation of drug use. Once people have used, we’re just providing basic harm reduction services. The observation is just a small part of our work.

Is the observation illegal because of the federal “crack house statute”?

Yes.

Has there been any progress toward getting that statute repealed?

Everybody’s waiting for the results of the Safehouse lawsuit. A Safehouse win wouldn’t eliminate the crack house statute, but it would definitely open the door to show how wrong it is.

When you’re talking to people who still say that overdose prevention centers are enabling drug use, how do you respond?

I probably have five different responses. The biggest one for me lately is talking about why these folks are going to use. The OPCs have almost 3,100 registered participants. We’re working with folks who are already currently using. We’re doing everything possible to keep them alive. Once they say to us, at any point, that they want to stop, we respond immediately. We go into action right away, so we are in no way enabling.

On an average day, how many people come to OnPoint?

If we’re talking specifically about the OPC, sometimes a few hundred. It varies. But if we’re talking about the whole organization, we see many, many more people than that.

When people come to OnPoint, what services are they usually seeking?

When people walk into the space, right away, most people who are here to visit go, “Wait a minute, where’s the drug use?” The door opens, and they see people having coffee, having a meal, watching a movie. We serve up to five meals a day.

If someone comes in to use the OPC, they’ll voice that, and if they’ve been with us before, we’ll sign them in. We ask a series of questions before they enter: What are you going to use? How much? If you weren’t here, where would you use? A large percentage of them will say they would have used in the alley around the corner of their block, inside a restaurant bathroom, or in a park nearby. These are key questions, so we can report back to the community—we’ve had almost 70,000 instances of drug use, and so that’s 70,000 instances that didn’t happen in the streets.

What happens after intake?

They enter the room, and they use. Again, this is one program in an array of many. We have case management, mental health services, low-threshold medical services, hepatitis testing and treatment, HIV testing and treatment. We’re opening a pharmacy, and that will not only service our people but all the members of the community. We have a holistic program that provides acupuncture, acupressure, some bodywork, and sound therapy, and that’s also open to the whole community. We’re opening a barber shop and salon free of charge.

What about things like beds and bathrooms?

We have a respite room now, that allows people to get eight hours of sleep—something many of them haven’t had in years. So if someone comes in and wants to use the restroom or take a shower, they’ll give us their clothes and we’ll wash them. We’ll give them nice, fresh socks. They can take a nice nap. These are the kinds of humanizing experiences that are going to impact people. What I know from my 31 years of work is that people stop using when they start to believe in themselves or feel better about themselves. So we love on them. If it’s someone’s birthday, the staff will give them cake, and sing. You’ll see big tough men—folks who look mean—cry like children, because people are singing for them. The drug use is the least interesting thing that happens in our world.

Does OnPoint model itself on overdose prevention centers in other countries?

Kailin See, our senior director of programs, ran OnSite in Canada, and helped open a couple of other sites. So we had an advantage with her being here. We didn’t have to reinvent this tool. We did make obvious adaptations for running a center here in the States.

What’s an example of an adaptation you made?

There was no way that we would get the entire city police department to agree to what we wanted and needed from them—but we realized, we don’t need the entire city yet, we just need the two precincts in the neighborhoods where we operate to respond in this way.

How do they respond so that they’re helpful to you?

Prior to us opening, if they saw someone outside who was using, they would arrest them. Now, the police make a referral. They bring people into us. They hand them a card that says, I’m not here to arrest you, I’m here to refer you to OnPoint. So that relationship has been beyond amazing.

Are you optimistic that the overdose crisis will get better?

I do have confidence that we’ll get there. My concern—we couldn’t get any money to address HIV for a while. We kicked and screamed, but society saw primarily gay men, and they didn’t have the love for them. And then they saw what we referred to at the time as injectable drug users, and that was another group society didn’t necessarily care about. It wasn’t until Ryan White contracted HIV that, all of a sudden, we had money put into research and care. I don’t want the world of harm reduction to have to wait for our Ryan White.

This interview has been edited and condensed.