Welcome to the oldest part of the metaverse

Welcome to the oldest part of the metaverse

Cunning miscreants nested thousands of objects in one place to create “black holes” that crashed the game.

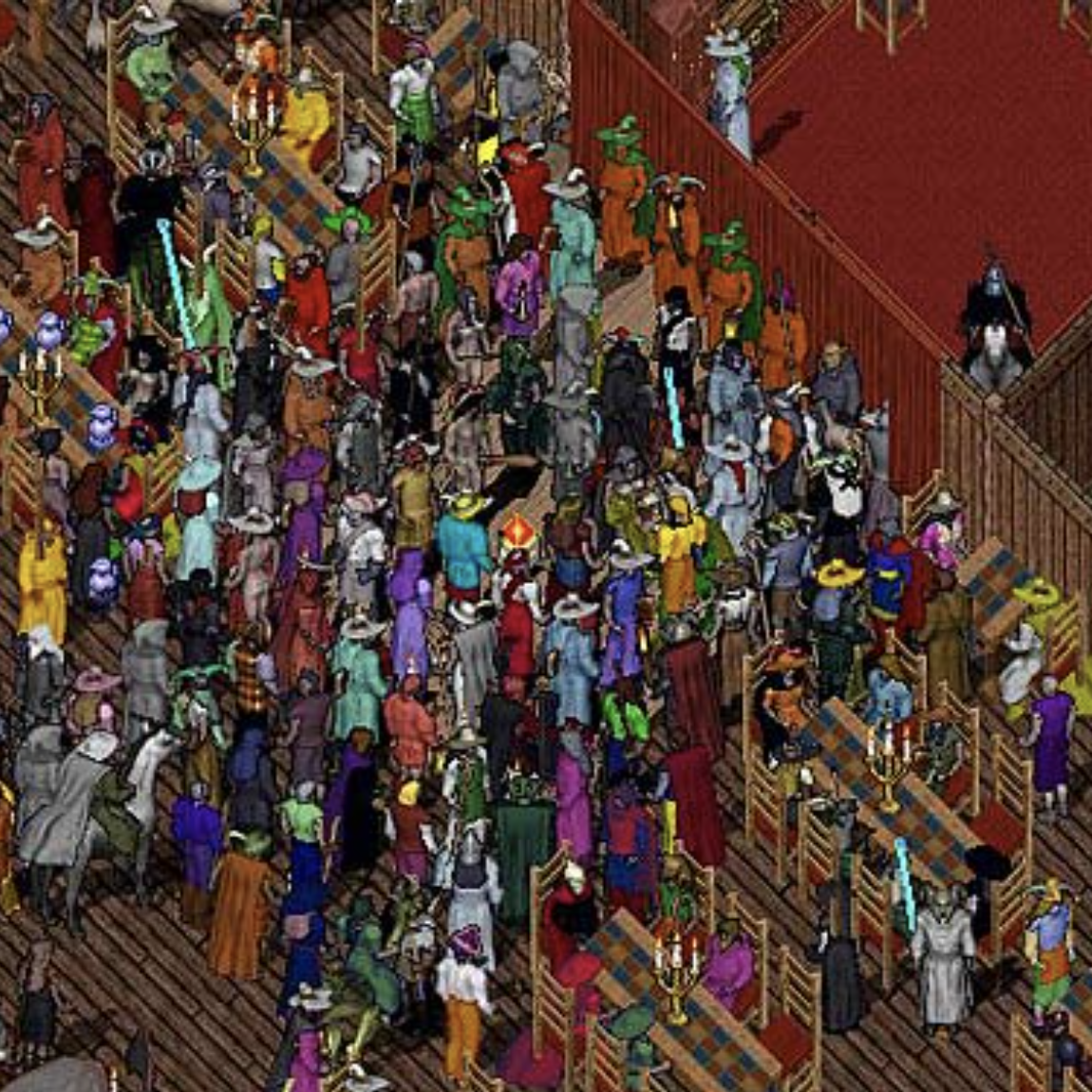

Yet it was quickly dawning on Origin that it was no longer merely a tech company. It was a government. And before long, that government presided over a population of more than 100,000 subscribers—larger than Charleston, South Carolina. Without the civic institutions that exist in real life, like school boards and labor unions, there were no outlets for players to express their wishes and feel heard. So Koster and the team set up “House of Commons” sessions where concerned citizens could chat directly with developers. The lobbying was fierce. Mages wanted spells to be stronger and swords to be weaker. Swordsmen wanted the opposite. There was no way to please everyone—no brilliant technical answer. The only path forward was the hard work of actual governance: communication, compromise, and transparency.

The most urgent policy question was what to do about murder. Garriott’s concept for Ultima Online stressed the freedom to role-play both good and evil, so the game enabled players to attack, rob, and kill each other. But the kingdom had turned into a slaughterhouse, with roving bands of powerful “player killers” butchering anyone who strayed outside the major cities—whose computer-controlled guards were invincible protectors in town but would ignore banditry even one step outside their jurisdiction. Although resurrection was possible, anything characters carried when they died could be stolen. So when curious new subscribers lost everything on their first trip into the woods, many logged off and never returned.

Again, Koster sought to empower players through richer simulation—establishing a bounty system that let victims put prices on murderers’ heads. Undeterred, the outlaws treated the bounties list as a leaderboard. Several more rule changes followed, including a reputation system that tracked players’ actions and applied penalties to disincentivize killing. Yet players found numerous loopholes to torment each other in ways the software wouldn’t notice.

A major challenge for the developers was figuring out what was actually happening in the first place.

In 2000, Garriott and Koster both left the company, and with subscriber attrition still severe, Origin opted for a drastic solution. It split the world into two mirror-image realms—Felucca, where nonconsensual violence remained possible, and Trammel, where player-versus-player combat was strictly opt-in. The move remains bitterly controversial, with critics saying it eliminated the sense of peril that made UO unique. But users voted with their feet and their dollars. Almost immediately, the great majority of Britannians migrated to Trammel. And with players free to choose which experience they wanted, subscriptions swelled to 250,000.

Concurrent with the player-killing epidemic, an economic crisis had also been unfolding. The game’s resource system had initially been a closed loop, with fixed amounts of gold and raw materials available. Servers would generate such goods on assorted trolls, zombies, and lizardmen that would spawn in savage wildlands or deep in foul dungeons. By killing them, adventurers could claim this treasure. Resources that players consumed or gold they spent at AI-run shops would go back into an abstract pool that the server would draw from as new monsters spawned. This system broke down almost immediately, though, as players mindlessly hoarded everything they could get their hands on—preventing fresh treasure from appearing. But when Origin changed its policy and disconnected the loop, monster loot became a firehose of wealth into the economy, and hyperinflation followed.